Why is uptake of the measles vaccine so low?

It’s difficult to avoid the subject of measles at the moment. The year has already seen reports of outbreaks across the United States, news of thousands of British children missing their vaccines, and the head of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring that the world is headed for ‘a measles crisis’.

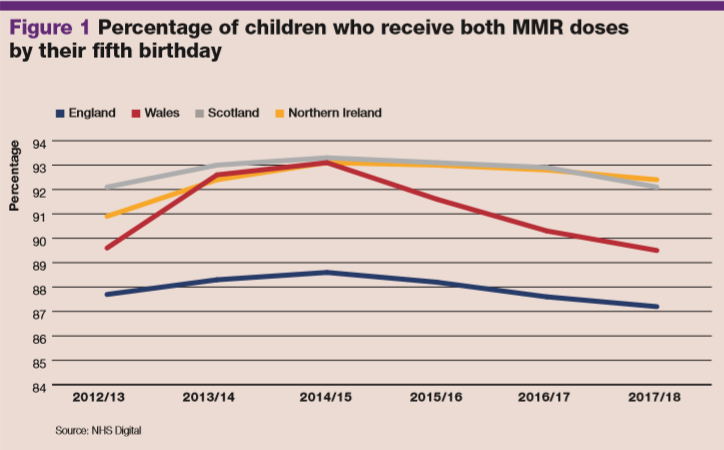

The UK isn’t helping when it comes to the predicted ‘crisis’. Since 2012, it has consistently failed to meet vaccination targets for children receiving both doses of the measles vaccine by their fifth birthday, and the most recent figures have shown a four-year low in vaccine uptake by the age of two in England.

The MMR-autism scandal

If you asked the average member of the public what they associate with the words ‘MMR vaccine’, the name Andrew Wakefield would likely come to mind. Described by one academic journal as potentially ‘the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years’, the MMR-autism scandal caused widespread panic and led to a significant drop in vaccine uptake in the years that followed the publication of Wakefield’s ill-fated Lancet paper in 1998.

Given the extensive coverage of the scandal in the press and the prevalent position of anti-vaccination groups in the news and social media, you’d be forgiven for assuming that false messaging about vaccination is one of the main drivers behind the lack of measles vaccine uptake.

But north London GP Dr Ellie Cannon believes that access to vaccination services is a bigger issue for today’s general practices. ‘Although there’s an impression that anti-vaxxers or vaccine refusers are to blame, that’s not thought to be the main cause for the lack of uptake. It has more to do with ease of access [to services],’ she says.

‘There are many groups of people who are vulnerable – certain ethnic groups, travelling families, people with chaotic lifestyles – who are not being vaccinated. It’s because of a lack of access to appointments; for example, if they have difficulty registering with a GP or getting to appointments at certain times. It’s not [always] what we think – logistics, organisation and access are barriers for these groups.’

Despite vaccination coverage rates in England creeping back up since the all-time low of 79% recorded in 2003 post-Wakefield, coverage remains lower than the 95% target in many parts of the UK. Why are so many children still not being vaccinated against measles?

Related Article: ‘Patients not prisoners’: Palliative care nursing behind bars

Unvaccinated

A UNICEF report published earlier this year found that an estimated 527,000 children in the UK missed the first dose of the measles vaccine between 2010 and 20171, which the heads of both UNICEF and the WHO described as

a ‘measles crisis’. Due to the highly infectious nature of measles, they said the infection can be considered ‘the canary in the coalmine of vaccine-preventable illnesses’.2 The WHO recommends a coverage rate of 95% for the MMR vaccine for measles elimination, but statistics released this year by NHS Digital show a decline in vaccine uptake in England in recent years. Uptake of the first MMR dose by two years of age was 91.2% in England in 2017/2018, down 0.4 percentage points from the previous year.3 Coverage has continued to decline steadily in England since 2014.

A UK snapshot

England has not had coverage rates above the WHO-recommended level of 95% in years, reflected in the slow but steady rise in hospital admissions for measles. According to figures, 2012/2013 saw nearly 600 admissions for measles, with an average patient age of 13, potentially reflecting a birth cohort who missed their vaccinations in the wake of the autism scandal. Admission figures dropped in the two following years, with a low of 47 in 2014, but have risen to nearly 200 in the past year.

Vaccination rates have inversely followed the trend in admissions, with the rate of coverage dropping in England and the other devolved nations since 2012 (see figure 1). Wales, for example, has experienced an almost 4% drop in uptake in the past four years. Of all the nations in the UK, Scotland has consistently achieved the highest coverage, which the Scottish minister for public health says reflects the ‘hard work and commitment’ of the NHS in Scotland, although it was overtaken by Northern Ireland in the latest data release.

Rhona Aikman, a practice nurse in Gourock, west Scotland, believes health visitors may play a part in the high coverage. ‘The health visitor role has been more preserved in Scotland. I think that, and the relationship with GPs and practice nurses, if established, may help,’ she says. ‘Trust can make a big difference, and vaccination is more likely if parents have built a relationship with a healthcare team.’

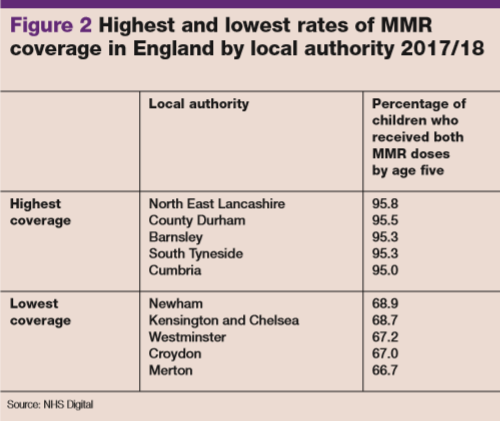

But it’s not all doom and gloom for England – despite having by far the lowest coverage in the UK, there are areas that manage to hit the 95% target, including North East Lancashire and County Durham (see figure 2).

County Durham-based practice nurse Julie Warin says that time and a personal touch help encourage people to get vaccinated. ‘When we relate our own beliefs and personal experience to the patients, they become much more receptive. My family have had the vaccine and patients really feel reassured when such examples are shared,’ she says.

‘We need to spend time with patients, reassuring them that we would not offer any vaccine with harmful effects.

‘Local updates around vaccines from the local GP federation, South Durham Health and the CCG also help. Up-to-date information empowers us to have more informed conversations with patients.’

Dr Kamal Sidhu, GP partner in Hartlepool, County Durham, adds: ‘Practices have very robust systems in place to ensure people are given optimum opportunity to have the vaccines. There is perhaps also less social media influence around here and patients, traditionally, have a lot of faith in their practice staff. Knowing the patient and their families has a huge part to play in this. Continuity is a powerful weapon.’

Barriers to vaccination

Related Article: Gypsy, Roma and Traveller healthcare: How can primary care serve this group?

Research by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), published in December last year4 in its Moving the Needle report on vaccine uptake across the life course, highlighted several possible reasons for the drop in coverage.

In a survey of around 2,600 UK parents, the report found that almost half of parents agreed that timing or availability of appointments were a barrier to access. Childcare duties were the next most popular reason for not accessing appointments, with just under a third of parents agreeing this was a barrier.

The report found that uptake was lower in smaller ethnic communities; for example, in Charedi Jewish families in north London. It found that Charedi families struggled to access vaccination appointments due to large family sizes, with lots of small children needing to be vaccinated or cared for at once. As such, birth order is inversely associated with vaccination status in this community.

Dr Cannon thinks there is more to be done with vulnerable groups. ‘There’s a group of stretched and vulnerable parents who are having a hard time accessing vaccinations, who may get the reminders for boosters, for example, and it’s a bad time or they’re unable to make an appointment and they’re just not going to try again. You might try again if you’re incredibly health-literate, and you’ve got privilege and time on your side, but you’re not going to try again if you’re in a vulnerable family.’

Public Health England (PHE) has also urged general practices to take steps to improve access for those at risk of not attending for routine immunisations. In an interview with the Pharmaceutical Journal5 earlier this year, Jamie Lopez Bernal, a consultant epidemiologist in the Immunisation and Countermeasures Division at PHE, said: ‘While vaccine hesitancy may be a factor for a small minority of parents, we know from our parental attitudinal surveys that confidence in the immunisation programme is high – the proportion of parents with concerns that would make them consider not having their child immunised has been at an all-time low for the past three years. Timing, availability and location of appointments have been identified as barriers to vaccination by parents and healthcare professionals.’

The RSPH report also found that false information about vaccines and a fear of side effects is a factor, to some degree, in the lack of uptake. Around two in five parents said they were ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ exposed to negative messages about vaccination on social media, rising to one in two in those with children under five years of age.

It highlighted some ‘concerning’ attitudes towards vaccination, with almost a third of 25-34 year olds surveyed agreeing that vaccinations are promoted by the healthcare system for pharmaceutical company profit. In addition, it found that of the 20% of parents who chose not to vaccinate their eligible child against influenza, almost half did so because they believed the vaccine wouldn’t be effective.

Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair of the Royal College of GPs, believes that vaccination education is a vital aspect of increasing vaccine uptake, which will ultimately help the NHS to achieve the aims of the Long Term Plan.

She says: ‘There is a deeply concerning and misleading school of thought – especially prevalent online and across social media – casting doubt over the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Of all the fake health news out there, anti-vaccination propaganda is among the most damaging for our patients’ health and the health of society. One consequence is that we are seeing an increase in the number of cases of potentially deadly diseases, such as measles – a condition that we were on the verge of eradicating in the UK a few years ago.

Related Article: Raising the profile of social care nursing and encouraging research in London

‘We need strong, society-wide public health campaigns reassuring patients about how safe, effective and essential vaccinations are. We need to cut through the fake news with evidence-based, easy-to-understand health advice for patients so they feel equipped and confident to challenge any spurious claims they might encounter. With that confidence, they will be able to make sensible, informed decisions about the long-term health and wellbeing of their children.’

Dr Cannon, however, believes that access should be the most important area of focus for those working on the frontline. ‘There’s not much we can do to change the beliefs of anti-vaxxers,’ she says. ‘It is part of the reason for the lack of uptake, but it’s the part we probably can’t change.’

References

- Unicef.org. (2019). Over 20 million children worldwide missed out on the measles vaccine annually in past eight years, creating a pathway to current global outbreaks – UNICEF. [online] Available at: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/over-20-million-children-worldwide-missed-out-measles-vaccine-annually-past-8-years

- Ghebreyesus, H. (2019). Measles cases are up nearly 300% from last year. This is a global crisis. [online] CNN. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/15/opinions/measles-cases-rise-global-crisis-fore-ghebreyesus/index.html

- Screening & Immunisations Team, NHS Digital (2018). Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics, England, 2017-18. [online] National Statistics. Available at: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/55/D9C4C2/child-vacc-stat-eng-2017-18-report.pdf

- Royal Society for Public Health (2018). Moving the Needle: Promoting vaccination uptake across the life course. [online] RSPH. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/f8cf580a-57b5-41f4-8e21de333af20f32.pdf

- Andalo, D. and Connelly, D. (2019). Appointment availability is behind huge number of missed measles vaccinations, PHE expert says. The Pharmaceutical Journal. [online] Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news/appointment-availability-may-be-behind-huge-number-of-missed-measles-vaccinations-phe-expert-says/20206471.article?firstPass=false

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Isobel Sims looks at the reasons behind the dwindling coverage of the MMR jab