Bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis

Key learning points

- Vaginal discharge is normal for women of reproductive age

- Part of the initial assessment of both conditions should include a sexual history to exclude an STI

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis should be confirmed by swab

Some vaginal discharge is normal for women of reproductive age. The type and quantity of cervical mucus changes during the menstrual cycle as a result of hormonal fluctuations. Prior to ovulation when oestrogen levels rise, the cervical mucus changes from being thick and sticky in the non-fertile phase to a clear, wetter and stretchy discharge at ovulation.

The vagina is colonised with commensal bacteria, which are normal vaginal flora. Rising levels of oestrogen at puberty lead to colonisation of the vagina with lactobacilli, which metabolise glycogen in the vaginal epithelium to produce lactic acid, resulting in an acid environment with a pH <4.5.1

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common causes of abnormal vaginal discharge in women of childbearing age. A prevalence of 12% was found in pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic in the UK and 30% in women undergoing a termination of pregnancy.2 It is characterised by an overgrowth of mixed anaerobic organisms that replace normal lactobacilli, leading to an increase in vaginal pH of >4.5. BV is not a sexually transmitted infection (STI) but there are associations between BV, STIs and other genital infections.

Men do not generally get BV and it is important to explain the condition to women in case they think they are the only one affected, and a partner might accuse them of being unfaithful.

Bacterial vaginosis

| Signs | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Thin white discharge coating the walls of the vagina | Offensive fishy smelling vaginal discharge |

| Generally no signs of inflammation | Not associated with soreness, itching or irritation, As many as 50% of women are asymptomatic |

Diagnosis

Nurses should be aware that the most common causes of vaginal discharge are physiological, for example BV and candida, but STIs should also be considered.

If a woman presents with a vaginal discharge that she feels is different from what she normally experiences, this should be assessed by taking a clinical history. She may, for example, fear she has a more serious condition such as cancer or an STI and you should manage this in a sensitive manner.

Part of the assessment must include a sexual history to exclude the risk of an STI. Individuals under the age of 25 years, or who have changed their sexual partner or had more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months, are at a higher risk of an STI.

The sexual history should include:

Related Article: Prescribing in England to be led by a single national formulary

- Number of partners.

- Gender of partners.

- Sexual activities.

- Use or non-use of condoms.

General history should include questions about the following:

- What has changed.

- Onset and duration.

- Odour, colour and consistency of discharge.

- Itching.

- Factors that exacerbate it, for example sexual intercourse.

- Pain.

- Dysuria.

- Any abnormal bleeding.

- Pelvic or abdominal pain.

There are two main methods of diagnosis:

- At least three of these four criteria are present for the diagnosis of BV to be confirmed:

- Thin, white, homogeneous discharge.

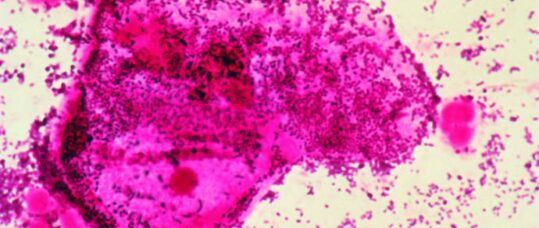

- Clue cells on microscopy.

- pH of vaginal fluid > 4.5.

- Release of fishy odour on adding alkali.

- Gram stained vaginal swab.

BV may exist with the presence of other abnormal discharge, for example candidiasis, trichomoniasis and cervicitis, therefore investigations to reach an accurate diagnosis are important.

The result of the history should also help in the decision to screen for STIs.

Treatment of BV

Treatment for BV is generally very effective if taken according to instructions:

- Metronidazole 400mg twice daily for five to seven days, or

- Metronidazole 2g as a single dose, or

- Intravaginal metronidazole gel (0.75%) once daily for five days, or

- Intravaginal clindamycin cream (2%) once daily for seven days.

Oral metronidazole is usually well tolerated and an inexpensive therapy. While intravaginal metronidazole gel and clindamycin cream have similar efficacy, both are more expensive.

The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) states in its national guidelines that there is no evidence of teratogenicity from the use of metronidazole in women during the first trimester of pregnancy and symptomatic pregnant women should be treated in the usual way. Women with additional risk factors for preterm birth may benefit from treatment before

20 weeks gestation.

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) recommends that women who are pregnant or breastfeeding may use metronidazole 400mg twice daily for five to seven days or intravaginal therapies. A 2g stat higher dose is not recommended in pregnancy or for breastfeeding women.

Complications of BV

- It has been linked with an increased risk of HIV in a study of pregnant women.

- The prevalence of BV is high in women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

- BV is common in some populations of women undergoing elective termination of pregnancy and is associated with post-operative endometritis.

- BV has been associated with an increased incidence of vaginal cuff cellulites and abscess formation following transvaginal hysterectomy.

- In one study, BV was associated with non-gonococcal urethritis in male partners.

- There are no studies investigating the possible role of BV in the onset of PID following the insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device.3

Advice for patients

Patients should be advised not to drink alcohol during metronidazole therapy and for at least 48 hours afterwards because of the possibility of a disulfiram-like (an abuse effect) reaction.

- Metronidazole enters the breast milk and may affect the taste. Women should be advised of this.

- Woman should be advised that following treatment, BV may recur.

- Provide a leaflet to support verbal information. The FPA does a good, clear leaflet.4

- Vaginal douching, which is common in some cultures, should be avoided as this changes the vaginal flora and may predispose women to BV.

- There is no need to treat sexual partners, and no need for test of cure.

- When prescribing for women with HIV using antiretroviral medication, nurses should refer to the Liverpool Pharmacology Group interactions website.5

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is very common among woman of reproductive age and is caused by overgrowth of yeasts; Candida albicans in 70-90% of cases, with non-albicans species such as Candida glabrata in the remainder. Between 10-20% of individuals will be asymptomatic.6

The presence of candida in the vagina does not necessarily require treatment unless the woman has symptoms. It occurs most commonly when the vagina is exposed to oestrogen and is therefore more common during the reproductive years and pregnancy. VVC can be found in non-sexually active women and is not classified as an STI.

None of these signs and symptoms should automatically indicate that an individual has VVC and evidence from laboratory tests should be used to confirm the diagnosis. Other possible diagnoses may include dermatitis, allergic reactions or lichen sclerosus.

Men with candidiasis may complain of itching and soreness under the foreskin or the tip of penis, redness, a thin or thick discharge and difficulty in pulling back the foreskin.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

| Signs | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Discharge, typically like cottage cheese in appearance, non offensive | Vulval itch |

| Oedema | Vulval soreness |

| Erythema and fissuring | Vaginal discharge |

| Superficial dyspareunia (pain on intercourse) |

Diagnosis

A vaginal swab should be taken from the anterior fornix.

Related Article: Advice on Guillain-Barré risk for adult RSV vaccine updated by MHRA

In order to aid diagnosis the nurse should take a general and sexual health history as described for BV.

VVC is more common in individuals who are pregnant, or who wear tight-fitting synthetic materials, are taking antibiotics, have uncontrolled diabetes, or any condition where the immune system

is compromised.

Treatment of VVC

There are several antifungal therapies available, including:

- Fluconazole capsules 150mg every 72 hours for three doses.

- Clotrimazole pessary 500mg once a week.

- Clotrimazole cream can be used locally until the patient’s symptoms resolve.

Advice for patients

The individual should be given a leaflet to support verbal information, and as with BV the FPA leaflet is helpful here.

Advise the patient to avoid local irritants, for example perfumed soaps, and to avoid wearing tight-fitting synthetic clothing.

References

1 FSRH. Management of vaginal discharge in non-genitourinary medicine setting 2012 p2. fsrh.org

2 BASHH. UK National Guidelines for the management of bacterial vaginosis 2012 p3 bashh.org.uk

3 BASHH. UK National Guidelines for the management of bacterial vaginosis 2012 p4 bashh.org.uk

4 FPA (formally Family Planning Association). Thrush and Bacterial vaginosis fpa.org.uk/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-help/thrush-and-bacterial-vaginosis#bacterial-vaginosis

5 The Liverpool Pharmacology Group. Drug interactions website at hiv-druginteractions.org

Related Article: Quick quiz: Management of COPD

6 European guideline on the management of vaginal discharge p1 iusti.org/regions/europe/pdf/2011/Euro_Guidelines_Vaginal_Discharge_2011.Intl_Jrev.pdf

7 FSRH. SRH skills for nurses fsrh.org/careers-and-training/srh-essentials

8 BASHH. UK National Guidelines for the management of bacterial vaginosis 2012 p4

9 BASHH. STI and HIV courses bashh.org/education-careers/bashh-sti-hiv-course

Further learning

- Education and training for nurses with no knowledge of sexual health can access the one day skills course at the FSRH, this is run nationally and further details on the FSRH website.7

- BASHH website also has competency skill courses on STIs.8

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

The vagina is colonised with commensal bacteria, which are normal vaginal flora.