Eating disorders in young people

Key learning points

- Eating disorders have very serious short-term and long-term consequences

- Nurses play a crucial role in supporting young people with eating disorders and in early intervention for young people who are developing eating disorders

- Being able to recognise an eating disorder early could greatly improve the individual’s chances of recovery

Eating disorders are a group of psychological disorders that, when not treated effectively, can result in a range of serious medical consequences, such as cardiac arrhythmia, oesophageal tears and even death.1,2

Eating disorders can affect people from any background, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation. Adolescent men and women aged between 13 and 17 years old have a higher risk of developing an eating disorder.3

The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) characterises six main classifications of eating disorder: pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.4 Eating disorders were the second most common diagnosis in children and adolescents in 2014, as stated by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) Tier 4 Report.5 The three most common eating disorders are anorexia, bulimia and binge eating.

Anorexia nervosa diagnostic criteria:4

- Restriction of energy intake, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory and physical health.

- Intense fear of gaining weight, becoming fat or persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain.

- Disturbances in the way in which body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current body weight.

Mortality rate

Over time, the risk of death due to complications of anorexia is estimated at 6-15%, giving it the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder.6

Treatment

Evidence suggests that family therapy is at the forefront of successfully treating adolescents with anorexia nervosa.7 Often referred to as the Maudsley model, it emphasises the role of the family in helping a young person recover from a disorder, and includes psychoeducation about nutrition and malnourishment.7 The approach helps to build a therapeutic reliance between a young person and their family as well as support the young person to establish a level of independence relevant to their development age.

Related Article: Diagnosis Connect service will link people to advice from charities

Cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED) can include family and individual sessions. Through personalised treatment plans, the sessions encourage healthy eating, mood regulation and relapse prevention, as well as combating anxieties over body image.3

Dietary advice and implementing meal plans is crucial in encouraging weight restoration. As a result, weight restoration will improve physical and psychological symptoms, and increase the quality of life for the young person.3

Medication such as antidepressants or antipsychotics can be used, but this should not be offered as a sole treatment for anorexia nervosa.

Bulimia nervosa diagnostic criteria:4

- An episode of binge eating is characterised by the following:

– Eating in any period of time an amount of food larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period.

– A sense of little control over eating during the episode.

- Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics or other medication, as well as fasting or excessive exercise.

- The binge-eating and compensatory behaviours both occur, on average, at least once a week for three months.

- Self-evaluation is disproportionately influenced by body shape and weight.

- The disturbance does not occur entirely during episodes of anorexia nervosa.

Prevalence

It has been estimated that between 1-2% of adolescents present with bulimia,8 with estimates as high as 4-7% for women in western countries for full or partial bulimia,9 and 0.5% in men.10 The average age of onset for bulimia is 15.7-18.1 years old,11,12 with recent trends suggesting that the mean age of onset is decreasing.13

Treatment

- Bulimia-focused self-help, such as CBT-ED, helps explore the impact bulimia has on the young person’s life and encourages motivation for change. CBT-ED teaches young people to be mindful of their feelings, thoughts and behaviours associated with the eating disorder.

- Evidence also states the effectiveness of family therapy in treating bulimia, with outcomes being greater than those of CBT.7

- Dietary advice and encouraging normal eating behaviours help reduce the symptoms of bulimia.

- Medication can be used to reduce the symptoms, but should not be used as a sole treatment for bulimia.

Binge-eating disorder diagnostic criteria:4

- An episode of binge eating is characterised by the following:

– Eating in any period of time an amount of food larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period.

– A sense of little control over eating during the episode.

- Binge-eating episodes are associated with three or more of the following:

– Eating much more rapidly than normal.

– Eating until feeling uncomfortably full.

– Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry.

– Eating alone because of feeling embarrassed.

– Feeling disgusted, depressed or very guilty after eating.

- The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for three months.

- Binge eating does not occur entirely during the course of bulimia or anorexia.

Prevalence

There is evidence to suggest binge eating is more prevalent in young children who are overweight and affects around 2-3% of people, more than that of anorexia or bulimia.14

Treatment

- Binge-eating-focused self-help programmes such as CBT-ED can be offered individually or as part of group sessions. The focus is around offering dietary advice and includes monitoring nutritional intake and weight. Body image issues are also addressed as part of the programmes.

- These programmes implement daily food intake plans and learning to recognise binge-eating cues and triggers to avoid relapse in the future.

- Medication should not be offered as a sole treatment for binge-eating disorder.

How to spot warning signs

Related Article: CVD prevention must be national health priority, says report

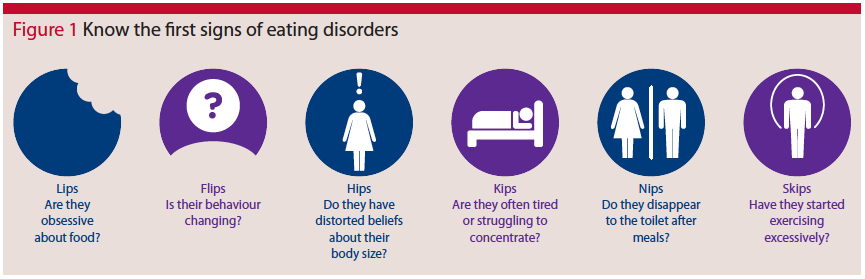

Figure 1 shows the six easy-to-remember signs of eating disorders that B-EAT (beat eating disorder) uses.

Figure 1: B-EAT’s first signs for eating disorders

Further signs and symptoms that require intervention are:3,9

- Two consecutive missed menstrual cycles.

- Lanugo hair.

- Calorie counting and controlling portion sizes.

- Increased weighing, checking body in mirrors and sensitivity around body image.

- Recently become vegetarian or vegan.

- Unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Other mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and self-harm.

- Physical signs such as malnutrition, poor circulation, palpitations and fainting.

- Unexplained hypoglycaemia or electrolyte imbalances.

- Abdominal pain associated with restricting intake or vomiting.

- Teeth decay, sore throat or swollen glands.

SCOFF questionnaire

The SCOFF screening tool was designed by Professor John Morgan at Leeds Partnership NHS Foundation Trust to detect the potential presence of an eating disorder.15 Answering ‘yes’ to two or more of the following questions could be

a possible indicator of an eating disorder.

- Do you ever make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortable full?

- Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than one stone (6.4kg) in a three-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that food dominates your life?

Authors:

Megan Nichols is a senior assistant psychologist,

Bev Kirwan is a mental health nurse and clinical service manager,

and Petar Stermsek is a psychology intern.

The authors all work for the CYP Family Eating Disorder Service at Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

Related Article: Postnatal contraception advice reduces the risk of back-to-back pregnancies

References

- Rome ES, Ammerman S. Medical complications of eating disorders: An update. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:418-26

- Zipfel S, Sammet I, Rapps N, et al. Gastrointestinal disturbances in eating disorders: Clinical and neurobiological aspects. Auton Neurosci 2006;129:99-106

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment (NG69). NICE; 2017:1-41

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Virginia;APA:2013

- CAMHS Tier 4 Report Steering Group. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) Tier 4 Report. NHS England;2014:1-35

- Lock J, Le Grange D. Help your teenager beat an eating disorder. New York;Guilford Press:2015

- Jewell T, Blessitt E, Stewart C, et al. Family Therapy for Child and Adolescent Eating disorders: A Critical Review. Family Process Journal 2016;55:577-94

- Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, Prevalence & Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012;14:406-14

- Le Grange D, Schmidt U. Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa in adolescents. J Ment Health 2005;14:507-97

- Hudson J, Hiripi E, Pope H, Kessler R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;61:348-58

- Fairburn C, Cooper Z, Doll H, et al. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:659-65

- Herzog D, Keller M, Sacks N, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in treatment seeking anorexics and bulimics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31:810-8

- Favaro A, Caregaro L, Tenconi E, et al. Time trends in age at onset of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1715-21

- Fairburn CG. Overcoming Binge Eating: The Proven Program to Learn Why you Binge and How You Can Stop. New York;Guilford Press:2013

- Morgan J, Reid F, Lacey J. The SCOFF questionnaire: a new screening tool for eating disorders. West J Med 2000;172:164-5

Resources

- B-EAT UK’s national eating disorders charity – b-eat.co.uk

- FEAST families empowered and supporting treatment of eating disorders – feast-ed.org

- NEDA National Eating Disorder Association – nationaleatingdisorders.org

- AED Academy of Eating Disorders – aedweb.org

- Young MINDs – youngminds.org.uk

- Fixers young volunteers – fixers.org.uk/fixing-eating-disorders.php#menuAnchor

Nursing in Practice Events visit 12 locations across the UK and cover topics such as mental health. If you would like to learn more please visit nursinginpractice-events.co.uk

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Eating disorders are a group of psychological disorders that, when not treated effectively, can result in a range of serious medical consequences, such as cardiac arrhythmia, oesophageal tears and even death.