Giving sound food advice for infants and toddlers

Key points

- Nutrition during the early years has an enormous impact on an individual child’s health, growth, IQ and even their future job status, and also affects families and the wider community.

- Getting food habits right from the start can help to reduce the risk of obesity as well as fussiness.

- Nurses have a crucial role to play in supporting parents and carers and empowering them to make healthy choices about the food they offer to their children.

Complementary feeding, or weaning, is the first step in helping children develop a good relationship with healthy food. It isn’t just replacing a baby’s milk feeds but complementing them, as they master the skills of eating solid foods. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Department of Health (DH) agree that breastfeeding should provide the sole source of nutrition for the first six months to achieve optimal growth, development and health.1,2

Complementary feeding, or weaning, is the first step in helping children develop a good relationship with healthy food. It isn’t just replacing a baby’s milk feeds but complementing them, as they master the skills of eating solid foods. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Department of Health (DH) agree that breastfeeding should provide the sole source of nutrition for the first six months to achieve optimal growth, development and health.1,2

Before this point, most babies are not ready to, nor do they need to, start solids. However, using professional judgment, it is important to take into account individual development; some babies might be ready to start weaning before six months, and if they are showing all of the signs, then it’s fine to advise starting. However, evidence suggests that it’s best to wait until the baby is at least 17 weeks old as, before this time, the digestive tract and kidneys might not be developed enough to cope with solids.

Delaying the introduction of complementary foods can be equally problematic. Body stores of some nutrients, such as iron, start to run low and so the baby needs to start getting nutrients from family foods, with the aim of getting most of their nutrition from family foods by the age of 12 months.

Research has also shown that introducing a range of textures early on is crucial, not only because biting and chewing help to develop the muscles in the mouth and tongue that are needed for speech development, but because the variety helps to prevent the development of fussiness as children grow older.3,4

Fortunately, the days of adding rusk to a baby’s milk bottle have gone, but approaches to weaning are still the topic of intense discussion. ‘Baby-led’ weaning is the term coined around 2003 by health visitor Gill Rapley. This unstructured approach is based on a baby being offered solid foods to feed themselves. Some research has found that this approach enables babies to regulate their own food intake.5

‘Responsive feeding’ is when a carer responds to the cues a child gives when eating, such as turning the head away from food that is offered, pushing food away or saying no. This involves trusting the child’s appetite cues, which might achieve healthier weight gain. However, concerns have been raised about the nutritional adequacy of baby-led weaning and there is no clear consensus.6 The most pragmatic approach appears to be incorporating some of the principles of encouraging finger foods and self-feeding, alongside more traditional spoon feeding of family foods to ensure as wide a variety as possible. This middle ground approach is the advice given by DH.

| Foods to take caution with for babies and toddlers |

|---|

|

What is a balanced diet?

Related Article: Diagnosis Connect service will link people to advice from charities

For adults, there are clear guidelines, shown on the Eatwell Plate about what makes up a balanced diet. Having a balanced diet as a family helps children to learn to enjoy a balance too, so that by one year old, children are eating family foods, and everyone can benefit.

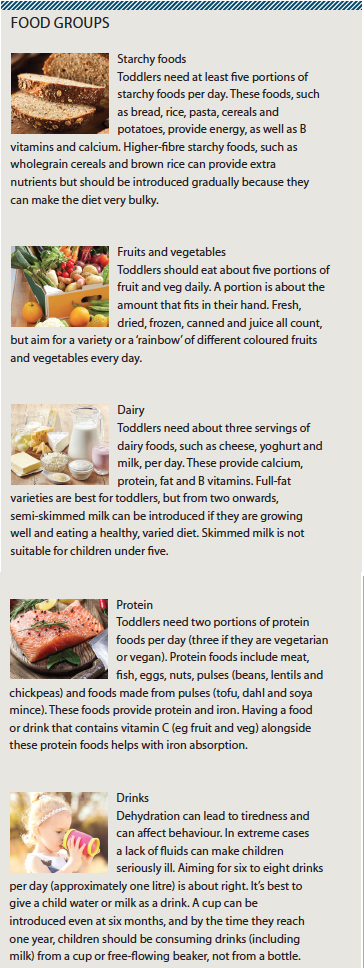

Toddlers and pre-school children are developing rapidly, so it’s important to ensure they are eating well and getting all the calories and nutrients they need, as well as developing healthy habits. As

a guide, toddlers need three meals and two or three snacks a day, made up of foods from the four main food groups (see box, right). It’s also important to get these in the right balance and in portion sizes that are just right for a toddler’s needs.

Some parents get very concerned about the times when their child seems to barely eat anything. It’s important to reassure them that this is normal. A toddler’s appetite does fluctuate – one day they may seem to be hungry and eating almost all the time, and the next day they might eat much less. Portion sizes should be guided by appetite. Giving small portions with the offer of extra when they are still hungry is better than giving a bigger portion and expecting them to ‘clear the plate’ every mealtime.

Fussy eaters

Some parents become very worried about fussy eating, but the important message is that it’s normal for children to refuse to eat certain foods sometimes. The peak time for this is between the ages of two and six. This may manifest as reluctance to try new foods, but can also be rejection of familiar foods, even if they have previously been eaten without any fuss.

The key is to stay calm, and reassure the parent that this is quite normal and usually passes. Nearly all children are capable of learning to like a variety of foods from the four main food groups, and if foods are at first refused, it’s important to try again another time.7

Parents have the important job of providing a variety of healthy foods – including established favourites and some new foods. The child’s role is to decide which ones to eat – or whether to eat at all on that occasion.

Reassure parents that it’s very rare for a child to make themselves go hungry. Offering a piece of fruit for a pudding if not much of the main meal is eaten, and then waiting until the next meal, makes sense; it isn’t advisable just to keep offering an alternative meal.

Other tips for dealing with fussiness include:

- Offer a variety early on to encourage familiarisation with a variety of foods.

- Keep offering foods even if at first they are rejected – it can take up to 15 tries to accept a new food.

- Avoid offering treats or ‘junk’ foods regularly, and don’t use these foods as rewards.

- Give children a choice between healthy option A and healthy option B.

- Don’t fill them up on milk.

- Be a role model for healthy eating as much as possible.

- Try to sit together to eat and avoid distractions at mealtimes.

- Ignore food refusal and simply remove the plate to avoid stress.

- Praise good food behaviour.

- Avoid force feeding.

- Offer small portions and allow seconds.

In terms of continued support, some parents might find it useful to keep a food diary to discuss with their nurse. The usual growth and development monitoring to ensure that this is normal will be a reassuring way to illustrate that there is still adequate nutrition, even if the dietary variety is lacking at times.

| Food allergy |

|---|

|

Food allergy is rare. The foods most likely to trigger a reaction are cow’s milk, soya, eggs, wheat, gluten, nuts, peanuts, seeds, fish and shellfish. These foods should be introduced only after the age of six months, in small amounts, and one at a time so that any reaction can be quickly spotted. |

Overweight and obesity

Related Article: CVD prevention must be national health priority, says report

Childhood obesity is a serious public health concern – in the UK more than one pre-school child in five is estimated to be overweight or obese.8 They are more likely to go on to be overweight or obese adults, as well as struggling with emotional and psychological problems, and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers.

Recognising and dealing with it in early years is far easier than dealing with it at a later date. The longer a child is overweight, the more established and extreme that excess weight is likely to become.

Sometimes it’s difficult for parents to recognise if their child is overweight. The NHS BMI calculator is a useful tool for parents to check if their child is a healthy weight. Any concerns should also be raised with the GP, who may be able to signpost to other services and healthy family lifestyle programmes.

References

1 World Health Organisation. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. London:WHO;2001

2 Department of Health. Introducing solid foods. London:DH;2011

3 Coulthard H, Harris G, Emmett P. Delayed introduction of lumpy foods to children during the complementary feeding period affects child’s food acceptance and feeding at 7 years of age. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2009;5:75-85

4 Grimm K, Kim S, Yaroch A et al. Fruit and vegetable intake during infancy and early childhood. Pediatrics 2014;134:S63-9

Related Article: Postnatal contraception advice reduces the risk of back-to-back pregnancies

5 Rapley G. Baby-led weaning: transitioning to solid foods at the baby’s own pace. Community Practitioner 2011;84:20-3

6 Cichero JAY. Introducing solid foods using baby-led weaning vs. spoon-feeding: A focus on oral development, nutrient intake and quality of research to bring balance to the debate. Nutrition Bulletin 2016;41:72-7

7 Hetherington M, Schwartz C, Madrelle J et al. A step-by-step introduction to vegetables at the beginning of complementary feeding. The effects of early and repeated exposure. Appetite 2015;84:280-90

8 Department of Health. Childhood obesity: a plan for action. London:DH;2016

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Complementary feeding, or weaning, is the first step in helping children develop a good relationship with healthy food. It isn’t just replacing a baby’s milk feeds but complementing them, as they master the skills of eating solid foods.