How to approach an HIV consultation

Shaun Watson gives advice on handling HIV consultations in primary care

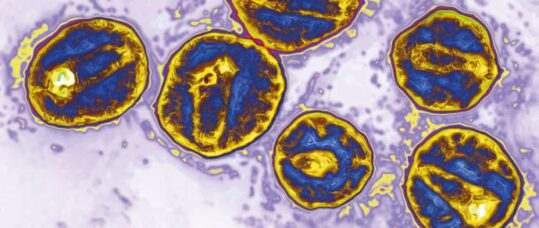

The landscape of HIV is changing from an initial life-limiting acute infection to a long-term condition with a normal lifespan.1-3 Over recent years there has been a fall in annual HIV rates, thought to be due to the use of medications to prevent HIV (pre-exposure prophylaxis), the use of antiretrovirals to suppress the amount of virus in people with HIV (undetectable = untransmittable) and the immediate use of antiretrovirals.4,5 However, people are still acquiring HIV and late diagnosis (when the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm at the start of antiretroviral therapy) is still an issue. The later someone is diagnosed, the poorer the immune response and prognosis.6,7

Late diagnosis is more frequent in older people. In the UK in 2016, 31% of 15- to 24-year-olds were diagnosed late, rising to 63% of over-65s, although the greatest absolute number of late diagnoses occurred in 35- to 49-year-olds, in whom the percentage was 45%.4,6 Testing for HIV in people who may be at risk therefore remains important. Over the decades, HIV testing has become easier to carry out, not only in sexual health clinics but also via home-testing kits and in GP practices, A&E, and community venues such as drop-in centres and churches. There are many HIV testing kits on the market – some are via blood spot (finger-prick or dry blood testing) and others via oral swabs. Most HIV point-of-care test kits will give a result in five to 20 minutes. The type of test available will be dependent on where you work and local policy.

Who should you test?

The answer is everyone who is sexually active, but unfortunately stereotypes may kick in, so an HIV test may be readily offered to a gay man in a monogamous relationship but not to the married 80-year-old man or the recently divorced 63-year-old woman, where discussing sexual health and sexual risk may be too embarrassing or not high on the list of concerns. Therefore, skilled communication is key in situations where you may be talking about sex as well as potential risk. An environment where the person feels safe to be open and honest about their risk is important so that the recently divorced woman who is dating but not using condoms (as she can’t get pregnant) and the 80-year-old married man who has been having unprotected sex with men can feel free to be honest with you and trust that you will not judge their decisions. See the box (below) for recommendations from the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH).

The BASHH guidelines also cover the frequency of testing and indicators of potential HIV infection. There are many indications such as bacterial pneumonia, peripheral neuropathy, oral candidiasis, weight loss of unknown cause, hepatitis B and C, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, anal cancer, cervical cancer and lymphadenopathy. A complete list is available in the BASHH guidelines.

Related Article: QICN bids farewell to Dr Crystal Oldman as she retires from CEO role

All too often people who present with a late diagnosis have attended primary and secondary care services and their symptoms have been missed, or treated but not followed up.9-12

Deciding to have an HIV test may be something that happens after long consideration or on the spur of the moment. Both decision processes may bring out differing reactions to positive or negative results. When talking to someone undertaking an HIV test the main aim of the initial discussion is to gain informed consent. Unlike the early days of HIV testing, lengthy pre-test counselling is not required unless the person has questions and needs time and reassurance to talk about their decision.

The main points to discuss before an HIV test are:

- The benefits of testing – what treatments are available if the result is positive and the implications for long-term health (no longer a death sentence, normal lifespan).

- Details of how the results will be given.

- What does an HIV negative or positive result mean? If negative, the need for further testing and risk avoidance, if positive what are the next steps? If you offer a test and it is refused, it’s important to discuss why as the patient might have false information or fears about the possible implications of a positive result (work, insurance, criminal prosecution).

| BASHH guideline recommendations8

Universal HIV testing is recommended in all the following settings:

An HIV test should be considered in the following settings where diagnosed HIV prevalence in the local population exceeds two in 1,000 population (see local Public Health England data):

HIV testing should be also routinely offered and recommended to the following patients:

|

Considerations and tips for HIV testing

1 – Be non-judgmental

This may be the first time the patient has been asked to talk openly and honestly about their sex life, risks, who they had sex with, and where, when and what they enjoy. Ask them how they identify their gender and sexuality rather than labelling what you perceive it to be. This can be complex but there are good resources available online (glaad.org; transmediawatch.org). You may not agree with someone’s decisions or life choices and what a person tells you in a consultation may challenge your values, but how you respond when a patient talks about their sex life may affect whether they access your, or any, sexual health service again.

2 – Body language

Related Article: England’s domestic supply of learning disability nurses projected to end by 2028

Think not only about what you say but your body language and facial expressions. All too often we hear stories about a healthcare professional who has looked shocked or disgusted by what a patient has told them. Try to get a full picture of what occurred, with whom and the actual or perceived risks. Unfortunately, there are still myths about HIV, and for some kissing or touching may be the only described risk. People often romanticise what happened to make them feel better in recalling the story and although this can be a useful way for them to get through a stressful situation, if they do not fully own their risks you might not be able to offer correct advice. The role of shame and embarrassment should not be underestimated.

3 – Mind your language

It’s best practice to work with what the person is telling you in language they understand. This may mean that you reflect back to them using the words they have used. You may find this uncomfortable, but try not to medicalise sex and change the language to something you find more comfortable. For example, in the early 1980s the first literature on HIV and sexual risk published for men who have sex with men used phrases such as ‘unprotected active/passive anal intercourse’, which for some meant nothing. The words these men used and understood to describe the sex they had were thought to be too coarse – ‘ass’, ‘fucking’, ‘top, ‘bottom’, ‘bareback’ or ‘raw’. Research has discussed the importance of addressing an audience using their own language, stating that when it came to safe-sex messages for gay men, ‘an arse was an arse and a fuck was a fuck’.13

Words used to describe sex, the sex organs and the sexual act are many and change over time depending upon age, where you live, your culture or religion. If you don’t understand, ask – ‘when you say the word “fucking”, can you explain to me what you mean?’ Don’t forget that one person’s full-on sex is another’s foreplay. If you aren’t comfortable using explicit language you could negotiate – ‘when you were talking about sex you were talking about a rash on your “cock” but I find it easier to say “penis”, is that okay with you?’ Clarify if this sits well with the person you are talking to; if not use the language they use.

4 – Be confident

Positive HIV results are falling but there will always be a first time that you have to deliver a result. Knowing beforehand why a patient wants to test and how they would feel if the result was positive will help. Do they know other positive people? How do they feel about HIV? Good preparation and a good pathway for positive results means you won’t be flustered by a positive result. Know the next steps, where should they go for support, further testing and care.

Shaun Watson is a community HIV clinical nurse specialist at Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust and the chair of the National HIV Nurses Association

Related Article: Not enough specialist nurses to provide palliative care in rural communities

References

- Date, H. L. (2018). Optimising the health and wellbeing of older people living with HIV in the United Kingdom. Lung cancer, 15, 05.

- Lundgren, J. D., Borges, A. H., & Neaton, J. D. (2018). Serious Non-AIDS Conditions in HIV: Benefit of Early ART. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(2), 162-171.

- Poorolajal, J., Molaeipoor, L., Mohraz, M., Mahjub, H., Ardekani, M. T., Mirzapour, P., & Golchehregan, H. (2015). Predictors of progression to AIDS and mortality post-HIV infection: a long-term retrospective cohort study. AIDS care, 27(10), 1205-1212.

- Price, B. (2005). Practical guidance on sexual lifestyle and risk. Nursing standard, 19(27).

- Public Health England (2018) Trends in new HIV diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2017. Accessed online 28 Jan 2018 at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/738222/hpr3218_hiv17_v2.pdf

- Brown AE, Mohamed H, Ogaz D, Kirwan PD, Yung M Nash SG et al (2017). Fall in new HIV diagnoses in men who have sex with men (MSM) at selected London sexual health clinics since early 2015: testing or treatment or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) Euro Surveil. 2007; 22(25).

- Lowbury, R (2018) A Roadmap for eliminating diagnosis of HIV in England. Halve It position Paper. Accessed online 28 Jan 2019 at http://halveit.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/halve_it_position_paper_FINAL.pdf

- May, M., Gompels, M., Delpech, V., Porter, K., Post, F., Johnson, M., … & Hill, T. (2011). Impact of late diagnosis and treatment on life expectancy in people with HIV-1: UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study. Bmj, 343, d6016.

- British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (2008) UK National Guidelines for HIV Testing. Accessed online 28 Jan 2019 at https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1067/1838.pdf

- Burns, Fiona M., Anne M. Johnson, James Nazroo, Jonathan Ainsworth, Jane Anderson, Ade Fakoya, Ibidun Fakoya et al. “Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis within primary and secondary healthcare settings in the UK.” Aids 22, no. 1 (2008): 115-122.

- Ellis, S., Curtis, H., & Ong, E. L. (2012). HIV diagnoses and missed opportunities. Results of the British HIV Association (BHIVA) National Audit 2010. Clinical medicine, 12(5), 430-434.

- Fisher, M. (2008). Late diagnosis of HIV infection: major consequences and missed opportunities. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 21(1), 1-3.

- Helleberg, M., Engsig, F. N., Kronborg, G., Laursen, A. L., Pedersen, G., Larsen, O., Obel, N. (2012). Late presenters, repeated testing, and missed opportunities in a Danish nationwide HIV cohort. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases, 44(4), 282-288.

Resources

- Find information on HIV clinics – www.aidsmap.com

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Shaun Watson gives advice on handling HIV consultations in primary care