Mycoplasma genitalium – an emerging global health threat

Nurse specialist in sexual health Sara Strodtbeck explains what nurses in primary care need to know about a sexually transmitted infection that experts have warned requires careful management in the community to prevent it becoming resistant to treatment

What is Mycoplasma genitalium

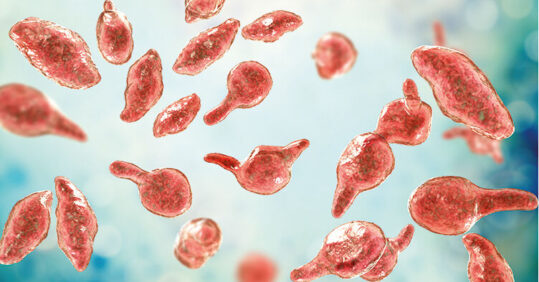

M. genitalium is an emerging sexually transmitted infection (STI). It is the most recently discovered bacterial STI and was first isolated in 1980 from urethral specimens of men diagnosed with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU).¹

It is bottle shaped and at 200-300 nanometres, it is the smallest known living organism capable of self-replication. The ‘neck’ of the structure ends in a tip that helps it attach to the epithelial cells of the genital tract.

M. genitalium is from a class of bacteria called mollicutes, from the Latin for ‘soft skin’, describing the lack of a cell wall.¹

How prevalent is it, and who is at increased risk?

Studies estimate the prevalence of M. genitalium infection in the general population is around 1-2%, lower than that of chlamydia.2,3 Surveillance of the infection in sexual health services began in 2015, and rates have increased significantly from 0.1% in 2015 to 12.8% in 2022.⁴ A recent audit in a sexual health service in Liverpool demonstrated a 11.1% prevalence in men* and 12.9% in women*.⁵

In common with many STIs, risk factors include younger age when starting to have sex, non-white ethnicity, smoking and increasing number of sexual partners. It is also associated with the detection of other STIs, with chlamydia the most frequently diagnosed co-infection.

How is it transmitted?

M. genitalium can be transmitted via unprotected sex. Most cases occur as a result of genital-to-genital direct mucosal contact, but there is evidence that infection can occur in the rectum following transmission via penile-anal contact. Carriage in the throat is rare.¹

What are the symptoms?

Related Article: Postnatal contraception advice reduces the risk of back-to-back pregnancies

Most people infected with M. genitalium will have no symptoms. In those who do, symptoms can be similar to those for other STIs such as chlamydia or gonorrhoea (see Table 1). Infection is closely associated with NGU and is thought to contribute to between 10% and 35% of non-chlamydial NGU in men. NGU is inflammation of the urethra with a cause other than gonorrhoea, diagnosed by examining a sample from a urethral swab under a microscope.

M. genitalium is also associated with cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in 10%-25% of cases.⁶ PID occurs as a result of infection ascending to the upper reproductive tract in women and can lead to increased risk of ectopic pregnancy and infertility if left untreated.

| Table 1 Signs and symptoms of M. genitalium | |

| Men (people with a penis) | Women (people with a uterus) |

| Urethral discharge | Abnormal vaginal discharge |

| Urethral discomfort | Painful bleeding between periods or bleeding after sex |

| Penile irritation | Inflammation of the cervix |

| Testicular pain | Low abdominal pain |

| Pain/burning when passing urine | |

| Rectal discharge or discomfort | |

How is M. genitalium diagnosed?

Diagnosis is made via nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) on urine samples or vaginal swabs. As the organism has no cell wall it is not seen on gram-stain microscopy, unlike other STIs including gonorrhoea. This means it cannot be diagnosed at first presentation for testing. Evidence suggests most people who have M. genitalium in their genital tract do not develop disease, so screening of asymptomatic individuals in the general population is not recommended, and could actually be harmful due to the risk of inappropriate use of fluroquinolone antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance (AMR).⁷ Furthermore, the low estimated prevalence of infection in the general population and in asymptomatic patients attending sexual health clinics does not support universal screening.³

The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) advocates testing in cases where M. genitalium could be a causative factor of disease, and in current sexual contacts of those diagnosed with it (see Table 2). Epidemiological treatment of sexual partners is not recommended, and only those who test positive should receive treatment.8

| Table 2 Who to test for M. genitalium | |

| Test | Consider testing |

| Diagnosis of NGU | Diagnosis of epididymo-orchitis |

| Signs and symptoms of PID | Sexually acquired proctitis |

| Current sexual partners of those diagnosed | Signs and symptoms of cervicitis |

What is the treatment?

M. genitalium is treated with antibiotics, with the type used depending on whether the infection is complicated or uncomplicated. Complicated infections are those with clinical signs and symptoms of PID, epididymo-orchitis or proctitis. Treatment is also dependent on whether the resistance status of the organism is known (Table 3).

AMR is a cause for concern globally and there are specific concerns in relation to STIs. In 2000, due to growing resistance to a number of antibiotics, a surveillance programme was established to detect and monitor AMR in gonorrhoea. More recently, a 2019 pilot study looked at the feasibility of a similar programme for M. genitalium.⁹

As indicated in Table 3, first-line treatment for uncomplicated infection is doxycycline followed by azithromycin. However, with M. genitalium demonstrating increasing resistance to the macrolide group of antibiotics, moxifloxacin, is an antibiotic from the fluroquinolone class, is the second-line choice. Fluoroquinolones have been reported to cause serious side-effects including tendon rupture, particularly in the ankle and calf, as well as mental health issues. Some side-effects may be long-lasting or permanent. As a consequence, all patients prescribed fluoroquinolones must be issued with written information from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.10

Treatment regimens may need to be modified in future, as evidence is emerging that M. genitalium is also becoming increasingly resistant to moxifloxacin.6

| Table 3 Treatment of M. genitalium | |

| Macrolide-sensitive or resistance unknown | Macrolide-resistant or failed treatment |

| Uncomplicated infection

Doxycycline 100mg twice daily for 7 days, followed by azithromycin 1g as a single dose then 500mg once daily for 2 days |

Uncomplicated infection

Moxifloxacin 400mg once daily for 7 days |

| Complicated infection

Moxifloxacin 400mg once daily for 14 days |

|

Are other types of Mycoplasma a concern?

There are more than 200 species of Mycoplasma. Mycoplasma hominis is another bacterium from the mollicute class that may be found in the genital tract but there is no evidence it causes disease in the same way as M. genitalium. It is often found in the urogenital tract in healthy individuals and symptomatic patients.11

There have been concerns about an increase in the availability of commercial assays, with online and private providers offering testing for M. hominis. BASHH recommends that this infection is not tested for as it is of ‘dubious significance’.12 As such, asymptomatic patients who present following a positive result for would not be offered treatment.

What is the take home message for community nurses?

While testing for M. genitalium would not usually take place in primary care settings, patients may present for treatment after receiving a positive diagnosis, or for testing as a sexual contact. AMR testing is automatically undertaken on any laboratory-confirmed diagnosis, but patients are advised to return for a ‘test of cure’ five weeks after starting treatment. Patients reporting symptoms suggestive of NGU or PID should be referred promptly to a sexual health clinic.

Related Article: ‘Concerning acceleration’ in drug-resistant gonorrhoea ahead of vaccine programme

It is imperative that epidemiological or empirical treatment for M. genitalium, particularly with macrolide antibiotics, is not given as this may contribute to increasing AMR. ⁹ Nurses working within primary care should continue to take opportunities to discuss sexual health and recommend regular STI screening for sexually active individuals and encourage people to access this for free from NHS providers.

*Author’s note: The terms ‘women’ and ‘men’ are used for brevity, on the understanding that these are also inclusive of trans, non-binary and intersex individuals.

Sara Strodtbeck is a nurse consultant at Axess Sexual Health Service, Liverpool

References

1 Taylor-Robinson D and Jensen J. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:498–514

2 Sonnenberg P et al. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma genitalium in British men and women aged 16–44 years: evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1982–1994

3 Baumann L et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in different population groups: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:255-262

4 UK Health Security Agency. Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England: 2022 report. tinyurl.com/UKHSA-STI

5 Strodtbeck S and Smith, K. Retrospective audit of patients tested for Mycoplasma genitalium in Liverpool Axess Sexual Health Service within a 12-month period. Internal report: Liverpool University Hospitals Foundation Trust. 2023; Unpublished

6 Jensen J et al. 2021 European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022;36:641-650

7 Kirby T. Mycoplasma genitalium: a potential new superbug. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:951–952

8 Soni S et al. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of infection with Mycoplasma genitalium (2018). Int J STD AIDS 2019;30:938-50

Related Article: Government to introduce HPV self-sampling for ‘under-screened’ women

9 Public Health England (2020) Mycoplasma genitalium antimicrobial resistance surveillance (MARS): pilot report. tinyurl.com/PHE-MARS

10 Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics (-oxacins): what you need to know about side effects of tendons, muscles, joints, and nerves. 2021. tinyurl.com/MHRA-FQs

11 Horner P et al. Should we be testing for urogenital Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum in men and women? A position statement from the European STI Guidelines Editorial Board. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32(11):1845-1851

12 British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. BASHH position statement on the inappropriate use of multiplex testing platforms, and suboptimal antibiotic treatment regimens for bacterial sexually transmitted infections. 2021. tinyurl.com/BASHH-multiplex

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom