Sara Rowbotham: ‘I’d gone past the point of polite’

Just ‘doing her job’ set sexual health specialist Sara Rowbotham on a path to national recognition. Here she talks to Nursing in Practice’s features editor Alice Harrold about whistleblowing and being played on TV by Maxine Peake

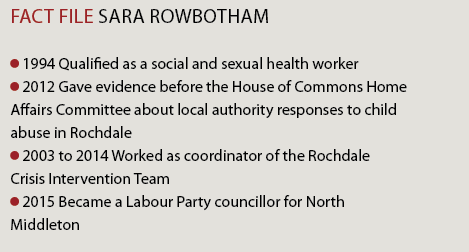

Born and raised in working-class Middleton to socialist parents, Sara Rowbotham worked in sexual health for young people for all of her career – until she led the team that brought the Rochdale abuse scandal to light and her life was changed completely.

Her team was the place that young abuse victims turned to in Rochdale when they felt unable to speak to the police. Ms Rowbotham continued to pursue the perpetrators, even asking the girls for their help to identify them.

A crisis intervention team co-ordinator from 2003 to 2014, Ms Rowbotham is now a Labour Party councillor for the same district that she fought so hard to change.

Between 2005 and 2008, hundreds of teenage girls were groomed and sexually abused by groups of Asian men in the Rochdale area. In 2012, nine of them were convicted of child abuse offences – but only after Ms Rowbotham convinced the Greater Manchester Police to investigate the grooming rings.

From 2004 onwards, she made more than 100 referrals to police and social services. But too often, the victims were dismissed as ‘unreliable witnesses’.

Ms Rowbotham’s conviction, tenacity and sense of humour are evident as soon as we meet in the Rose Court Hotel in Marylebone. We head to a place up the road with an outside area so that she can continue to smoke while we talk.

‘Fearless’ team

Ms Rowbotham recruited her own team, who worked with her for 13 years. ‘They were fearless in relation to young people and really, really good. I always thought I was good, but they beat the socks off me.’

‘Young people never actually came in and said, “I am being abused”. That wasn’t the situation.

‘We needed them to tell the truth in relation to their sexual health or else we couldn’t help them. The skill the workers needed was to make sure that the young person in front of them told us the truth very quickly, which they did.

‘They would describe incidents of unprotected intercourse with multiple people, adult men or in a group situation. What became really obvious is that it was without their consent. And even if they insisted that they did consent, actually they were too young to do so. They were all impressionable.

‘We started to hear the same names mentioned by different groups of young people that weren’t associated with each other. They’d all describe the same car or going to the same place.’

Hitting brick walls

Ms Rowbotham had made something she called the ‘Boyfriend Book’, in which she and her team kept records of all of the perpetrators and their details as given by the young people over the years. The book was eventually used in court as evidence.

It was frustrating for Ms Rowbotham to work so hard to get young people to trust her team with their experiences of abuse, only to have other state authorities such as social care and the police dismiss them.

Related Article: Food insecurity and obesity: a North-South divide

‘I think there are lots of judgments about young people’s sexual activity. There used to be definitions like “promiscuous teenager” or “dresses like a prostitute”,’ she says. ‘When I first started in Rochdale, that was a policy. It’s really judgmental and it makes it seem like a choice.’

‘And “promiscuous” [seems to be defined as sex with] “one more than you think is too many”. You might think three people in a week is a lot. I might think three in a year is a lot, so it’s a value judgment. But it only takes one episode of unprotected sex that isn’t consensual, surely?’

‘Some practitioners still talk about young people displaying “attention-seeking behaviour”. We need massive structural change in this country so that communities feel stronger, more empowered and more together, all of which will help individual self-esteem for girls and boys. It’s really difficult because so many services have been caught and slashed and removed.

‘I kind of think the age of consent should be 36,’ she laughs. ‘Because only by the time you’re 36 are you really able to make positive decisions about who you want to have sex with. You feel confident and comfortable about your own sexuality and how you express your sexuality. You’re able to say “yes” or “no” to the kind of sex that you want to have. Sex isn’t for children.’

Supporting the abused girls was a balancing act because they were speaking to Ms Rowbotham and her team voluntarily, and often weren’t aware that they were being abused. ‘Some of them were really quite defensive about it, saying, “He is my boyfriend, he does treat me nice, he does say nice things, he does buy me presents”, all of that. But of course, that’s because they were being manipulated,’ says Ms Rowbotham.

‘We would ask: “So you don’t know your boyfriend’s surname?” They are always really good clues. We’d say: “How old am I? If you think he’s 19, how old do you think I am?” That’s often a good indication of whether they really know.’

Talking to these girls ‘is a skill,’ she says, ‘because you have to not present like a police officer and you can’t interrogate them. It has to be quite subtle, but you’re getting as much information as you possibly can without them being bothered or alarmed.

‘We would often say to young people: “Have you met his parents? You know, if he’s really your boyfriend he’d want to show you off.” This one girl was taken blindfolded in a car to somewhere she didn’t know, taken up some stairs to these two very elderly Asian people who didn’t speak any English. He told her they were his mum and dad and then she was able to come back to us to say, “Yeah, I met his parents”.

‘It was all really clever manipulation stuff to convince her. She must have been incredibly valuable to him for him to go through that charade. We were flipping flummoxed then. Some young people really didn’t know they were being abused in that situation.

‘A social worker would come because I said, “We need to make this stop. I want you to have a nice life that is full of joy.”’ She continues. ‘So, of course, the social worker came round, did an initial assessment, didn’t actually meet the child, said there was no evidence [of abuse] and then buggered off again – which was tricky. They were aware of what was going on. All we could do was be persistent and consistent.’

After the abuse scandal broke, an independent serious case review was held in which, says Ms Rowbotham, she and her team were criticised for being ‘hard to work with’ and not following procedure.

‘We drove young people around in the car and said “Can you show us exactly where that happened?”, “Are they still there?”, “Would you take us to where they were?”. If we hadn’t done that, there wouldn’t have been evidence in court. So actually, thank God we did. The irony is, the serious case review criticised us for doing that.’

Court action

Eventually, Ms Rowbotham persuaded the Greater Manchester Police to investigate the issue seriously, leading to several arrests.

‘They brought men in to be interviewed by these police officers, who then identified, of course, that there had been potential crimes committed. The difficulty was that once they were arrested, the clock started ticking to collect the evidence.

‘The police allocated a serious incident team, as they do if there’s a murder. And they were tasked with finding as much evidence as possible on these men they had arrested.

‘I called all the staff in together and said, we’re going to be shit hot, we’re going to find this information. We’re going to see who’s connected and how they’re connected. And we did, really quickly.’

Following the team’s efforts, nine men were imprisoned in 2012 for inflicting targeted, systematic abuse on victims in Rochdale.

‘After the court case, however, my problem was they had only arrested nine [abusers] and they wanted that to be the end, as though that was it finished. And of course, it wasn’t finished.’

Ms Rowbotham then got in touch with the former MP for Rochdale, Simon Danczuk. ‘He initially said to go to the press, but that felt too uncomfortable. It felt like I would be breaching confidentiality. And yes, it might have been headline news, but that wasn’t anything sustainable. So instead, he wrote to the Home Office and to the then Prime Minister David Cameron.’

This led to Ms Rowbotham being asked to come to Parliament to give evidence and call for an independent inquiry.

‘I was supposed to go on the Thursday and I didn’t tell my organisation until the Tuesday. And of course, on the Wednesday, they sent the chief exec and the trust’s solicitor to see me and my boss to try to encourage me to speak about things in a particular way.

‘Thankfully, the trust solicitor said to me “Oh my God, that’s so exciting”. I think if he had responded differently, my whole approach to that day would have changed. I’m really grateful that he did respond like that because I was able to lay it all out on the table.’

That meeting led to ‘bigger conversations’ about grooming, abuse and the how the state authorities reacted.

‘But what didn’t happen immediately was that they didn’t reopen any investigations – and that became really frustrating. Surely the best way was to identify the perpetrators, find them and lock them up?

She pauses. ‘Can you ever have justice? I don’t even know. I think those men are paedophiles and we need them locked up. We need them away from children and out of our community.

‘I think we have to give the absolute maximum amount of support to those young people. I think they deserve compensation. They deserve rehoming. I think they need the best mental health support they can possibly get.

Related Article: Over one million children living in homes causing asthma and chronic illness

‘I think if those circumstances were repeated, then I would really actively encourage more victims to come forward.’

A wider platform

Following the flagship court case, Ms Rowbotham was approached by writer Nicole Taylor and director Philippa Lowthorpe, who also directed Call The Midwife, and were interested in telling her story.

The actions of Ms Rowbotham and her team have been told in the hit BBC drama Three Girls – a brave and unwavering portrayal of the real experiences of three girls who were victims of a circle of child abusers, which became the most-watched drama on BBC iPlayer in May.

I ask Ms Rowbotham what has changed since the drama aired. ‘I’ve probably had about 2,000 emails since it showed,’ she says. ‘A lot of those have been really nice people saying lovely things. And that’s amazing because I never thought anyone would say thank you.

‘And at my worst, I thought that nobody would ever say thank you. Now people have, it’s overwhelming.’

Ms Rowbotham has also heard from other professionals who want to whistleblow. ‘It’s really hard to hear that there are still people in the workplace that are struggling to get things done for something that they can see is wrong.

‘And then there are the people who are suffering now. So parents who are struggling with their children and people who are disclosing stuff that happened to them as a child. A proportion of those have been almost enlightened by the drama, and didn’t really realise that was the circumstance they were in.

‘I know Rochdale made a number of arrests after the first episode and that must have been because people came forward to report [their abuse].’

An average of 1.5 million young viewers watched each episode of Three Girls, not including BBC iPlayer views. ‘Parents have said to me “I’m making my children watch this”,’ says Ms Rowbotham. ‘The woman at the end of the road came over to say she has made her niece watch it. The niece is only 13 but she said to her, “You’ve got to sit down [and watch it] because this is what could happen”. I mean, we don’t want to scare them to death, for God’s sake, but I think there’s an element of education that is really helpful.’

Indeed, Ms Rowbotham says even the BBC was surprised by the impact of the drama. ‘I think they thought it was going to be a bit dark and not everybody would watch it, but that wasn’t the case. The numbers have been phenomenal.’

Personal implications

The stress of whistleblowing took its toll. ‘My hair was straight when all this started,’ she grins. ‘You know during the war when people had a really weird sense of humour? I think there was a big element of that for my team. That kind of banter was a real relief. It solidified us as a team. If we didn’t have each other, we wouldn’t have survived it as long as we did.

‘We all went through varying degrees of mental health upset. Acknowledging that we all had that level of vulnerability and we were all human, for God’s sake, allowed us to care about each other.’

Ms Rowbotham suffered for a long time with night terrors, eventually getting treatment from her GP, who diagnosed depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. ‘I had really awful dreams that my mum was stuck in a taxi and I couldn’t get her out. No matter what I did, I couldn’t get her out. She was stuck and I could see her there, her face up against the window.

‘Once I shared that with the team, they felt able to tell me stuff that they were experiencing as well.’

But after the abuse scandal came to light, Ms Rowbotham feels that she and her team were ‘deliberately excluded’ from conversations about the problems they had helped to uncover.

Related Article: Call for nurses to be central to a potential ‘Operation Paramount’ roll-out

‘They held a “Lessons Learned in Rochdale” conference and didn’t invite me,’ she says. ‘I didn’t contribute at all. One school nurse was invited – and she was the only representative from health. I don’t think she could attend because they only told her two days before.

‘I should have been celebrating and feeling vindicated, and my organisation should have championed the work of my team. We should have been Crisis Intervention Team Of The Year all over the country. We should have been a model of best practice, because we really were excellent practitioners.’

But instead, Ms Rowbotham feels that she and her team were ‘totally shafted. It was like they wanted to put us in a room and close the door so that nobody would know that we even existed.

‘I didn’t set out to be some kind of champion. And I wasn’t a maverick either, you know. I think I worked within a structure like everybody. I’d gone past the point of being polite.’

So contributing to Three Girls became a cathartic experience. ‘Working on the drama, having those conversations with somebody who really did believe me and was interested, gave me

a lot of confidence back.’

She also met Maxine Peak, who played her in the drama. ‘She came to the house and my mum grassed me up for everything I’d ever done wrong. Honest to God, she did! She told her about when I was really cheeky on the holiday we had when I was six. I was like, “What are you doing that for? It’s Maxine Peak, for God’s sake. That’s the flipping nation’s sweetheart in your living room!”’

Does she feel vindicated now? ‘I’m still not 100% sure I’ve got to a point of feeling vindicated. I don’t really know what vindication feels like, so I don’t know whether I’ve reached that point.’

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Just ‘doing her job’ set sexual health specialist Sara Rowbotham on a path to national recognition. Here she talks to Nursing in Practice’s features editor Alice Harrold about whistleblowing and being played on TV by Maxine Peake.