Wound care for leg ulceration

Key learning points

- Venous disease is the most common form of leg ulceration

- It is essential to establish the cause of leg ulceration to inform treatment

- There is robust evidence to support the use of graduated high compression for treating venous leg ulceration

Leg ulcers are the most common type of wound in the UK, accounting for 34% of all wounds.1 Most leg ulcers are caused by problems with damaged veins, which make it difficult for blood to return to the heart (venous leg ulcers). Skin breaks down or injuries fail to heal, or heal slowly and then recur repeatedly. A smaller proportion of leg ulcers are caused by insufficient arterial blood reaching the skin (arterial leg ulcers) or by problems with both the veins and the arteries (arterial/venous leg ulcers).

A minority of leg ulcers have unusual causes, such as cancer or other diseases.2 Leg ulceration results in great distress and suffering to patients, and most leg ulcer care is delivered in primary or community care settings.

Venous leg ulcers

Venous leg ulceration occurs when the veins struggle to return de-oxygenated blood from the lower legs to the heart. This is known as chronic venous hypertension and is caused by failure of the calf muscle pump, due to obstruction of the veins by thrombosis and incompetent valves in the veins. This leads to a backflow of blood (reflux) causing oedema, which leads to friable skin and skin breakdown (ulceration).

Venous ulcers usually occur on the gaiter area of the leg, are often ‘wet’, and may be accompanied by varicose eczema

Arterial leg ulcers

Arterial leg ulceration occurs when arterial disease interrupts the normal flow of blood to the skin, resulting in the skin breaking down. Arterial disease can be in the form of atherosclerosis (formation of plaques that narrow the lumen of the arteries), thrombosis (blood clots that can result from plaque formation), arteriosclerosis (when the arteries lose elasticity, resulting in the smooth blood flow becoming more turbulent, which increases the risk of thrombosis), or vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels and associated with rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus).

Related Article: ‘Patients not prisoners’: Palliative care nursing behind bars

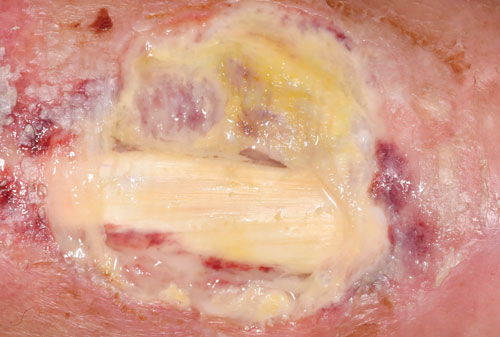

Arterial ulcers are typically deep, poorly perfused and may show some tendon

Other causes

Leg ulceration can be due to arterial or venous disease or a combination of both, but there are also some other, rarer causes. These include inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, unusual vascular or arterial diseases such as vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, Raynaud’s phenomenon, haematological diseases such as sickle cell anaemia, infection such as tuberculosis or tropical infections, and malignancy.

ABPI is necessary to assess arterial blood supply to the lower limb

Diagnosis and treatment

When treating leg ulceration, the priority is to identify the cause. As venous disease is the most common cause of leg ulceration, it is the most likely diagnosis – but it is important to exclude other causes, in particular significant arterial disease.

The most effective treatment for healing venous leg ulcers is graduated high compression (such as four-layer bandaging or compression hosiery), which more than doubles the chances of healing.3 However, high compression should not be applied to a leg that has an inadequate arterial supply.

A Doppler assessment of ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) should be undertaken as soon as possible to assess the patient’s arterial supply. A reading of 0.8 or above is generally regarded as adequate for the application of full compression.4 Patients with a reading below this should be referred to a vascular service for further assessment and treatment. Patients with signs and symptoms of more unusual causes of leg ulceration should be referred for a dermatological opinion.

Most patients with leg ulceration will experience pain, so they should be offered effective analgesia. The evidence suggests that dressings make no difference to healing, so simple low-adherent dressings are likely to be clinically and cost effective.5-7 Many patients with leg ulceration will have dry skin, so simple emollients should be applied to keep the skin supple. Patients with venous disease may have varicose eczema (pictured, top), which may require a steroid ointment.

There is evidence to suggest that oral pentoxifylline can promote healing of both venous and arterial leg ulceration, so this should be considered.8

Venous insufficiency is a long-term condition, so once healing is achieved patients will require ongoing treatment. Lifelong compression therapy should be offered (along with regular ABPI to check the arterial supply).9

There is also evidence that ablative superficial venous surgery can prevent recurrence, so patients should be referred for a vascular assessment.10

Related Article: NHSE confirms dates and eligibility for autumn Covid and flu jabs

References

1 Guest J, Ayoub N, McIlwraith T et al. Health economic burden that wounds impose on the National Health Service in the UK. BMJ Open 2015;5(12)

2 Morison M, Moffat C. Leg ulcers. In: Morison M, Moffat C, Bridel-Nixon J et al (eds). Nursing Management of Chronic Wounds Mosby 1997. p177-220

3 O’Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson E et al. Compression for Venous Leg Ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012. CD000265

4 SIGN. Management of chronic venous leg ulcers – a national clinical guideline 2010 sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/120/

5 O’Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ologun Y et al. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 CD003557

6 O’Meara S, Martyn-St James M. Foam dressings for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 CD009111

7 O’Meara S, Martyn-St James M, Adderley U. Alginate dressings for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 CD010182

8 Jull A, Arroll B, Parag V et al. Pentoxifylline for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012 CD001733

9 Nelson E, Bell-Syer S. Compression for preventing recurrence of venous ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 CD002303

Related Article: ‘Concerning acceleration’ in drug-resistant gonorrhoea ahead of vaccine programme

10 Barwell J, Davies C, Deacon J al e. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1854-9

Resources

Nelson E, Adderley U. Venous Leg Ulcers. BMJ Clinical Evidence 2016.

Wounds UK. Best Practice Statement: Holistic Management of Venous Leg Ulceration 2016 wounds-uk.com/best-practice-statements.

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Most leg ulcers are caused by problems with damaged veins, which make it difficult for blood to return to the heart (venous leg ulcers). Skin breaks down or injuries fail to heal, or heal slowly and then recur repeatedly.