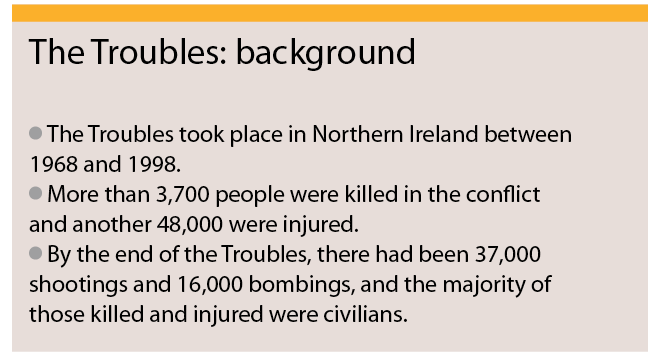

‘Some nurses were told to keep two walls between them and the gunfire’

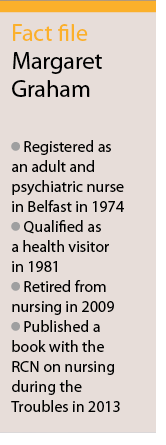

Alice Harrold talks to Margaret Graham, who worked as a health visitor in Belfast during the Northern Ireland Troubles and has dedicated her retirement to recording the stories of nurses during that period

What made you want to be a nurse?

I grew up in County Fermanagh, in the west of Northern Ireland, 10 miles from Enniskillen. I went to school in Fermanagh for a while and then my family moved closer to Belfast, and I finished my education there. My dad was one of five, and I had a whole lot of aunts who were nurses. One of my aunts was a health visitor, who was a great influence on me and she encouraged me to consider health visiting. She took me out and showed me what it was all about. She said that if I went into nursing then I would have to go to The Royal because that’s where she and all my other aunts had trained.

I ended up doing what they called a ‘combined scheme’ through The Royal and got a dual qualification in general and psychiatric nursing when I was about 22. Then I was a ward sister in The Royal for a bit, and then I went to Australia for a year. When I came back I switched to health visiting and then the rest of my career was mostly in the community in north and west Belfast. I had post at the Department of Health later on where I was a commissioning person for post-registration education.

Did you feel prepared when you qualified to go into the situation that you were going into?

No, we didn’t know. I had no concept at the time that The Royal was in the position it was — a triangular site between rival sides. I remember on my first day at The Royal, we went for quite a walk round the local streets and I looked up at the street names and thought, ‘These are the names I’ve been hearing on the news for the past couple of years’. My first night in the nurses’ home you could hear bomb fire outside. I looked out the window and you could see smoke. But you just normalised it so quickly and that’s how it was, and you didn’t know any different, and everybody else was in the same boat.

Whenever I got the train home, I would come out with a little overnight bag. All the streetlights had been knocked out so there was no lighting and I would just walk as quickly as I could up to the train station. It was probably around a mile away but I would do it in about 15 minutes.

Were you given any advice at that point?

I can’t remember anybody giving us any advice. Some of the other nurses would say that when there was a lot of shooting, they would have been told to lie in the corridors and told to keep two walls between them and the gunfire. Eventually a hospital bus was laid on for us and for outpatients to come to the hospital. It was a free bus that went up and down the Grosvenor Road because quite often when there was rioting or shooting or things like that the city buses would stop running to the hospital.

Do you remember your first day as a health visitor?

Do you remember your first day as a health visitor?

I do, we were given a whole pile of cards and the hardest part was actually finding a lot of the streets and finding your way around because you didn’t want to seem like an outsider asking strangers to find an address. A lot of the street names weren’t up and you only had a map to go off. On a lot of the estates the house numbers were out of order.

When I got going the thing that really struck me was the level of poverty and poor housing. Some of my families were in private rented accommodation in old Victorian terraced houses that were built for factory workers. There was one cold tap and an outside toilet shared by many families. I had nothing but admiration for how they were able to rear families in those conditions.

When the families in the community saw that you were trying to help them, you would get a lot of warmth from them. They were very welcoming. I’ve worked on both sides and regardless of the area, the families always seemed to trust the nurse and they always took it that nurses were neutral. You didn’t discuss politics or the Troubles or anything anyway. You were there to see the families and to assess what their health needs were and help with them.

How did the political situation impact on what the families needed from you?

Well you realised yourself sometimes that you would be saying to a mum, ‘The immunisations were due,’ for example but then you would quickly suss out that there’s maybe been an incident in the street or the father was imprisoned and there was a prison visit due, etc. You knew then that there wasn’t a chance at all that you were going to get many health enhancing messages through that day. So you just had to go with the flow at times. If there was something bad going on you might just sit and listen to let them talk through whatever situation they needed to talk through with you. But you would have been told sensitive information. People knew how much to tell you so as not to put you in an awkward position.

What kind of measures did you use to keep yourself safe?

There weren’t any official measures. We didn’t have personal alarms or even mobile phones, because they weren’t around in those days. And there was no system where we told a manager or anybody else where we were going.

Related Article: More nursing apprenticeships and changes to student travel expenses

Informally the team I was in would meet for coffee in the morning and we sort of vaguely said where we were going. Then we were always in at lunchtime or in the afternoon, so if anything had happened we would have known informally where everyone had been going that day. But if something was going to happen you would get a gut feeling and the atmosphere around the place would change. Some of the families might have said ‘Stay in this afternoon,’ or ‘Don’t be visiting up this way,’ because they’d got noise that something was going to be going on.

Did you have to become used to violence?

I don’t think you ever get used to it and every time you heard of another attack or a policeman blown up you would think ‘When is it all going to end?’ and ‘Can it get any worse?’ The Enniskillen and Omar bombs were major for us and those rocked you. It shakes you to despair and many of the times I wondered if I would ever have peacetime, which was part of the reason I went to Australia for a year, because I wanted to see what it was like. But when you come back home and settle into everything again, you have your own social life, you’re living, I was able to go out to the pictures, out to shows and go on holidays. So my social life wasn’t really curtailed, because at the end of the day, Northern Ireland has a population of 1.7 million or something like that at that time, and Belfast is a small place and quite often when anything happened, it was all very localised. There are people over here who say they were untouched by the Troubles, it just depended where they were. Where I worked happened to be badly affected but not where I lived.

What kind of support were you given?

There was no counselling and I don’t even know if people thought of post-traumatic stress. When I started nursing in the early 70s, we went straight into a nurses’ home that was on site at The Royal. So we were on site and many other sisters and staff nurses were just across the road in a tower block. Everything took off so quickly that you soon felt you were in it together. If anyone annoyed or upset you, when you came off duty, you piled into somebody’s room and you talked it through. So there was always a sense of being able to talk things through, informally, and I think in many ways nurses preferred to do that. Formal counselling wasn’t offered, oh gosh, maybe way into the 1990s or so.

After you retired you set about collecting stories from the Troubles in Northern Ireland for your book, Nurses Voices, which was published by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN). What was it like for you to revisit this period?

I think I always had a gut feeling throughout my nursing career that we would need to record what nurses did during the Troubles. I took early retirement because it gave me the opportunity to do what I felt needed to be done about getting narratives down. So when I retired in 2010, I joined the History of Nursing Network with RCN Northern Ireland. There I saw the nurses who had been senior sisters when I had been a student training at The Royal Victoria Hospital. While talking about recording the Royal’s history, I said, ‘We do oral histories of older nurses to have them on record in the archive. So I said to the sisters, “Well have you recorded yours?”,’ and they all said, ‘Oh no, we’re not old enough yet,’ and I said, ‘Well what about all that you did through the Troubles?’ and they said they’d been asked to do that, but didn’t really know where to start. So from there we planned to have focus groups in Belfast and then around Northern Ireland to collect the stories of nurses during the Troubles.

Some people whispered their stories but when we put them into groups they all said they felt comfortable talking because they had been through similar experiences. So many said that they’d never discussed it with their families – too many. Some people said that they had everything packed away in their head, in a box, and they were worried that if they talked about it, everything would come out. Other people said that they couldn’t wait to get their story written down because they just wanted somebody to know what it had been like for them. It was a cathartic exercise as we went round the Provence and I was really quite taken aback by the amount of raw emotion that was still there, even after nearly 40 years.

It was good to hear what other nurses around the Provence, especially those at the border, had experienced. We heard from nurses who were involved with both the Omar and the Enniskillen bombs. One of those nurses had lost all her friends. Hearing that really hit me.

So how did your family and friends feel knowing that you were going to be a nurse starting in the 70s, did that change how they felt about it?

Well, I think my dad might have quite liked to have seen me go to university but he didn’t stop me from doing nursing, because all his sisters and sister-in-laws were nurses. There was the family history there. My parents never said anything to me about the dangers of it, but a few years ago, cousins of mine from South Africa, who had been over at the time of the Troubles, said, ‘Oh your parents watched every newsflash.’ So I reckon they were probably worried enough. There was a bomb on the periphery of the hospital grounds once and there was a picture in the Daily Telegraph of some student nurses in uniform walking past the rubble to go on duty. I actually found a copy of that photograph in a scrapbook that my mother must have cut out. They never would have said ‘I don’t think you should be working up there,’ or anything like that, but I know they kept an eye on the news.

Did you think about staying in Australia at all?

I thoroughly enjoyed it, it’s a lovely country, but I wouldn’t have wanted to settle there. I missed the sense of humour at home. In nursing at times there was quite a bit of black humour and I just missed the craic and the friends that I had made throughout nursing here, so I came back home again.

Did you think about how you were putting yourself back in a difficult situation?

No. I think sometimes when you’re naturally living these things, you’re part of history. I was more taken aback by the social poverty than anything else.

I suppose looking back now, I didn’t fully appreciate at the time that the mothers I was visiting were probably children when all those street burnings were taking place and they had probably missed out on a fair amount of their own childhood. They didn’t speak to me about when they were growing up but there was a lot of things that you would have done to try and encourage them, such as getting them to play with their children and interact more. But looking back, they probably didn’t have that too much when they were children, at the very start of the Troubles.

The family was getting a lot more fractured. It’s a transgenerational thing, which we wouldn’t have been alerted to at that time, because we were all still in the middle of the Troubles, but you hear more of it now, once we’re in peacetime, about the transgenerational effect of conflict on families.

I suppose because my mum was a teacher, I was always keen to see children trying to achieve. So I asked parents what they would like their children to be, and what they hoped they would grow into and they were very clear in their response – they didn’t have dreams for them. Sometimes you would discover that the mother couldn’t read and then you think, ‘How are these kids ever going to get anywhere, if the parents can’t read terribly well?’

Why did you decide to go into community nursing during such unstable times?

In the hospital they’d send patients home and then about eight weeks later some of them would be back in again. It was a revolving door and I thought I would quite like to be out there to see what’s going on and to do something more in a preventative way. And I think working in the community gives you a greater sense of autonomy and it was something different. I think one of the best things about a nursing career is that there are so many pathways that you can go along.

North and west Belfast, where I worked, had one of the highest rates of people being killed in the Troubles, but it was an area of social deprivation, high teenage pregnancy rates, high rates of people with disability, poor housing, high unemployment, low education attainment, and all of this.

By the time I started in health visiting in the 1980s, although there was a lot of shooting still going on, there weren’t as many bombings all the time. Within health visiting, even though the Troubles were still on, we were able to try new things. So there was always a challenge to try and do something with a public health initiative, and in the eighties we had the capacity, we were able to try out community activities that might maybe make a difference to the area that we were working in.

By that stage we were all just used to working where we were working. In the Shankill Health Centre where I was, we’d all go for a cup of coffee at lunchtime and everyone said that they really loved working there and that they couldn’t see themselves working anywhere else. I suppose that just shows how normal it all became.

What kind of knowledge and skills did you need to have above and beyond your clinical background?

My aunt always said that you needed a bit of life experience, which is why she encouraged me to go abroad for a while before I came back and did health visiting. You had to have common sense as well. But the main thing was to have a bit of humanity and to be alert to the situation that you might be going into in any household, especially if the mum looked more stressed, agitated or distracted than usual. You learned never to ask a closed question but to always try to ask an open question that made them keep talking, rather than answer you with a yes or a no.

Did you need to know a lot of kind of local knowledge about each community, so that you could fit in anywhere?

Well I suppose we did. On the Shankill Road, the kerbstones were all red, white and blue and the Union Jacks were flying and the murals on the wall were all to do with the Loyalist side. When you crossed through what was called the peace wall through to the Falls Road side, the kerbstone colours and the flags changed and everything else changed. So you sort of learnt a bit better around knowing what communities you were in. You learnt to know a wee bit about your first communion on one side, and traditional days and the other days, obviously on the Shankill side. So you just didn’t do visits on the afternoon on the eleventh, because nobody was interested in seeing you. You also had to learn how to find your way around a maze of streets in different ways, with different exits and entrances for when there were roadblocks. That if you got stuck you would have another route out.

If you were a district nurse out and about, especially along the boarder, you were often getting stopped and checked, and it would hold up your day and your patients – and you had your own concerns too like who are you going to run into and will something happen that would affect you or your car and you’d be stuck.

Related Article: Nurses given ‘range of leadership opportunities’ in NHS 10-year plan

Were there things that frightened you?

It sounds awful to say but no, there weren’t. It was just normal. Most of us had never experienced what it was like outside of that. We were all in the same boat so we just got on with it. Everybody else was getting on with their job and you never thought anything else of it. I wouldn’t have worked anywhere else for the world and you know, if you’re able to connect with a lot of your families and help them and they see their appreciation, then you feel that you are achieving something.

The Troubles lasted so long and we were all so acclimatised to it that life just seemed normal. It is only on reflection that you realise how abnormal it all was and that none of us would want to go back there!

Community nurses were referred to some at the time as ‘Cinderellas’ – is that how it felt?

Well certainly where we were, we didn’t get a lot of extra resources. We got the basics but there’s only ever a certain amount of money in a pot and there was still probably a lot of money going into the hospitals at the time, for what was still going on. There wasn’t much left over for developing anything with nursing services in the community. I suppose a lot of community nurses would still say that today.

I think they talk about moving care from hospitals into communities, but community is not a cheap option and the money doesn’t always seem to follow the patients.

After the ceasefire happened, when Labour came into government in 1997, there was a bit more money around and where we had a Belfast regeneration organisation. And because of the complexity of the issues relating to where I worked you could bid for project money to try things out. We put in several different business cases we got money out. We put money into the programme to tackle teenage pregnancy. We put a team together that involved young people as peer educators to work alongside sexual health workers and the doctor because once we had the ceasefire it became easier to do evening work in the community and that project was very affective.

Are there are any lessons that nurses today could take from the experiences of all the nurses during the Troubles?

I think just it’s good to be able to share anxieties, to take time to discuss the ups and downs of the day and to reflect on your practice. It’s good to try to build up your resilience with your colleagues and to have a sense of humour – I think you have to have a laugh about something. Nurses today don’t have the facility that we would have had to meet together in the nurses’ home but it’s important to have some soft of support network so that you can speak things through and get a bit of reassurance.

What memories stand out for you the most?

Well I suppose of the things that stick in my mind is in say my third week when I started on duty, I went off the ward at lunchtime and when I came back on at five o’clock, I walked into the female ward where I had been and all the patients were missing and there was no beds. There had been a big bomb in town and we were getting people in so patients were being moved. I remember just being petrified because all I knew was how to feed a patient and how to make a bed. The wards were full of doctors and everybody was waiting for people to either come back from theatre or from patients we’d got from casualty to get ready to go up to theatre.

I also have several images in my head of people that were severely injured and one died and the other was just very bad brain injury that I had to sit with most nights on the night duty. It was only later on that it suddenly dawned on me that first year students would have been left looking after the most seriously injured patients for whom there was really no hope and that the more qualified nurse would have been looking after people who still had a chance.

There was a shortage of qualified staff and students were the main workforce at the hospital, and we were in at the deep end. But we had very good ward sisters and qualified staff who kept a good eye on what you were doing.

The Royal, and I expect the other hospitals, never had a problem with recruiting student nurses. The Royal always had a waiting list! The difficulty was retaining staff once qualified, as nurses often left to do midwifery or go back to their provincial hospitals or travel.

I remember the day when the ceasefire was announced and I was driving up the Falls Road and everybody was out cheering. I drove past The Royal and I remember just having a flashback of a lot of people that I had looked after and just thought well what would it be like now for all these families and the community as we had a new chapter for our Provence of cessation of violence.

In the early days there was a lot of optimism around and an awful lot of tears around as well. Everybody started coming to see where all the trouble had been and all the murals up and around north and west Belfast. There started to be a lot more community activity and get-togethers, trying to catch up on lost time. There were a lot of community development initiatives then to tackle education problems and health issues. Once there was ceasefire and then the release of prisoners, you’d go to see the families and there might be a man around the place where there hadn’t been before.

The families had persevered on their own for many years at that stage so you didn’t really know what was going to lie ahead for them. It was new for everybody. The one thing we did know was that the level of violence was going to drop. We were even able to develop some evening services like a 24-hour district nursing service and family planning clinics running after business hours. There was also a bit more assurance that staff would be safe at night.

Related Article: Government to develop ‘advanced practice nurse models’, says NHS 10-year plan

What sights or sounds bring you back to that time in your life?

It’s died down mostly now. It used to be every time, even on holidays, if I heard a bang – even if it was thunder – I would think ‘There’s another bomb.’ But that has gone with the years since the ceasefire. Thankfully I didn’t have too much dealing with anybody that was badly burnt because I know that the nurses who dealt with some of the bombs, when people were really badly burnt, can still be brought back there with the smell of burning.

I know that there are probably things stuck in my head that I have forgotten about because I would have said to myself at the time to just get on and do it. There are even some things that I would have been involved with that I don’t have a memory of now because I told myself to forget about them.

The good memories that stay with me are of the comradeship and fun, the friendships, and everyone pulling together when we needed to.

Going as a bunch of school-leavers into a nurses’ home, it was so regimented. You had your bedroom with communal baths and toilets. You were all together and you got to know people and you all bunked into somebody’s bedroom at night and had tea and biscuits or something like that. Eventually six of us moved out to a house together when we were twenty one – that’s when you were allowed to move out of the nurses’ home – and we had a great social life in the house and would have had lots of friends and all of that. We had really good craic and a laugh. Looking back I have no regrets about having trained at that time.

I can remember calling in for petrol years after I left the Shankill Road and one of the mums that I would have visited was behind the counter and she recognised me. Her family had done well and she was working. Over the years I bumped into a couple of my mothers that I would have visited who had gotten jobs, and their families were up and they’d managed to get themselves part-time work. They were just so pleased with themselves and that was great to see because it made such a difference to their psyche.

Do you consider the Troubles to be over now for you and for the patients you treated?

Well certainly things are a lot better than they were, we still hear about people getting knee capped and sadly there has been some shootings at prison officers and police by different groups. But Northern Ireland is such a different place today. It’s just unrecognisable from when I started there in 1971 and it’s so great. The place is full of tourists – it is just so different from before.

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom

Alice Harrold talks to Margaret Graham, who worked as a health visitor in Belfast during the Northern Ireland Troubles and has dedicated her retirement to recording the stories of nurses during that period