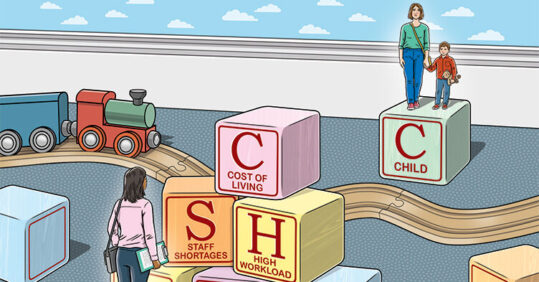

Against a backdrop of rising need and ever-tighter resources, nurses continue to push for babies, young children and their parents to receive effective care – but want more support and investment from the Government. Kathy Oxtoby reports

The cost of living crisis continues to have a significant impact on families, and the challenges that confront health visitors and nurses supporting babies, children and parents are greater than ever, practitioners have told Nursing in Practice.

A growing backlog of care arising from the Covid pandemic, and the pressing need to deal with more complex cases and conditions are just some of the pressures being faced.

While demand for services that support families with young children is escalating, the resources required to deliver that support are decreasing, with nurses reporting funding cuts and staff shortages.

In health visiting, for example, the level of pressure has become so great that in May, the Institute of Health Visiting (iHV) co-signed an open letter spearheaded by the NSPCC, calling on the Government to rebuild the health visiting service and improve access to mental health services for new parents.

The organisation said health visitors play a vital role in identifying parents who are experiencing mental health problems and in providing or arranging support, but that the workforce in England is ‘at an all-time low and there are not enough health visitors to meet the level of need’.

Executive director of iHV Alison Morton goes further, warning that the health visiting workforce is so depleted that she has recently heard of health visitors who are expected to handle a caseload of around 4,000 children, ‘which is clearly unmanageable’, she says.

Nurses have responded to the care backlog with new ways of working. In some areas, for example, practice nurses have been supporting health visitors with their workload, and continue to offer some virtual consultations to boost access to services. And nursing bodies are lobbying hard on behalf of children, campaigning alongside the NSPCC and other charities to highlight the shortfall in resources.

Nursing in Practice spoke to health visitors, school nurses and practice nurses to learn more about the problems they are up against.

‘Hidden backlog of unmet need’

While government policy might suggest the pandemic is over, for health visitors it is a different story, says Ms Morton. ‘What our members are telling us is that the impact of the pandemic is not over for babies, young children and families,’ she explains.

‘We’re only just starting to recognise the wider impact on the largely hidden backlog of unmet need – those “invisible” babies and young children, and vulnerable parents, including women with postnatal depression, who have always been a concern and who do not get the support they need,’ she says. The pandemic has meant some families have simply not been seen.

Despite health visitors’ best efforts, Ms Morton warns they are now ‘struggling to meet growing levels of vulnerability’ because of the workforce shortage.

‘Referrals are escalating, and the shortage of health visitors means we have less time to do brief interventions and build relationships with families,’ says a health visitor in the Midlands, who asked not to be named. ‘We’re also seeing a lack of early intervention because of the pandemic, which means families have got to crisis point before they come into contact with services, making it much harder to support them,’ she says.

In Cheshire, Hannah’s son, born in 2020, has yet to see a health visitor. ‘During the pandemic I was told there were no face-to-face visits. Just recently, I called about my son’s 18-month check and was told there were still no visits because of Covid. I’m now being forced to “go private” so that he can have a full check-up,’ she says.’

Even when checks are carried out face-to-face there is no guarantee they will be done by a health visitor. In the south of England, for example, one health visitor says two-year checks are being carried out by nursery nurses.

Ms Morton explains that the main drivers behind the shortage of health visitors are cuts to public health funding and workforce attrition – with people retiring or leaving the profession due to burnout, and insufficient training places to make up for the numbers lost.

Under-resourced health visiting services are resulting in a ‘postcode lottery’ of access to support, with the risk that new parents experiencing mental health problems are being overlooked because of the service’s ‘rapid deterioration’, according to the recent open letter to the Government co-signed by iHV.

This March, the Government said the five health visiting contacts mandated up to the age of two should be carried out face to face, amid concerns about virtual services not reaching the most vulnerable children. However, the letter states that ‘many families are not receiving the five health visiting reviews they are entitled to, or these vital checks are being delivered remotely, which makes it harder for professionals to identify perinatal mental health problems’.

Indeed, whether or not a family receives the five mandated health visitor contacts itself appears to be a postcode lottery. One health visitor in the south of England says she and her colleagues are doing more than the mandated five visits, while another in the Midlands says that while they are seeing families, ‘the picture varies very much across the country’.

Nurses, alongside nursing bodies and charities, are campaigning hard to raise awareness of the pressures facing health visitors. Ms Morton says iHV is advocating on behalf of babies, children, families and health visitors, as well as working with organisations like the Parent Infant Foundation ‘to showcase different, effective health visiting services to make people understand what the role involves and the positive impact it has’.

‘More money and more health visitors’ is what the iHV wants from the Government. ‘In the Autumn Spending Review, we joined with partners calling for a £500m ringfenced uplift in the public health grant,’ Ms Morton says. ‘This would start to address the national shortage of 5,000 heath visitors. We also need a focus on quality to end the postcode lottery.

‘It’s a false economy not to prioritise babies and children – if we don’t invest in them, we will pay the price for generations to come,’ she warns.

Concerns about child health support

General practice nurses (GPNs) are working ‘over their normal hours and still not getting through all their workload’, says Heather Randle, RCN professional lead for education and primary care.

Now that people are beginning to socialise more again, she says GPNs are seeing more cases of chickenpox, stomach bugs and other common children’s conditions.

More families are returning to their GP practice for face-to-face visits, some with multiple conditions that need treating. Bradford-based GPN Naomi Berry says she is catching up with referrals, and supporting distressed patients waiting for appointments in secondary care. ‘It’s the norm now to have to say, “Sorry you’re having to wait” – it’s upsetting and frustrating,’ she says.

Ada Allen, an advanced nurse practitioner based in Leeds, is finding that families are anxious about their health in the wake of the pandemic, which is resulting in an ‘escalation of demand’. But while demand is growing, numbers of GPNs are falling, she says, with ‘nursing colleagues taking early retirement or even ditching their permanent positions to do locum shifts in general practice’.

GPNs have concerns about whether families are getting sufficient child health support. ‘What I’m hearing from nurses is that they are still seeing problems around face-to-face contact with health visitors and school nurses,’ says Ms Randle. She says this is putting ‘more pressure’ on practice nurses, who are being asked about issues that health visitors would normally address.

Parents have told Ms Berry that they have not seen health visitors in person, and she is often questioned about access to baby clinics. ‘We’re doing as much as we can to try and offer as much support as we can, to answer parents’ questions and provide relevant information, but it’s difficult,’ she says.

Recognising the workload pressures facing health visitors, Ms Allen says she tries to support parents, giving them guidance and basic information on good nutrition, and, if necessary, referring them to a paediatrician. ‘Health visitors have been getting in touch with us asking for help with tasks because they are particularly busy, so we’ve been stepping up to do what we can to help,’ she says.

One way of helping to address the demanding workload is to educate parents, Ms Randle says. She reports seeing ‘some good work with self-care’, where GPNs are teaching parents how to deal with a high temperature or a child with vomiting and diarrhoea – ‘the conditions people can treat themselves’.

Ms Berry also points to a rise in ‘major poverty’ for many parents, as the cost-of-living crisis bites. She says: ‘We are looking to find ways to deal with this, including providing preventive and holistic care, which is more important than ever.’

Peer support for GPNs is on the increase, ‘but still needs a lot of work’, Ms Randle believes. ‘We should be giving every nurse in general practice supervision to reflect on their practice and to learn from it. And we should be making sure nurses are released from practices to do staff training.’ She says the Government ‘should be looking at this issue to bring on the general practice workforce’.

Workforce measures are vital to help GPNs cope with the growing need from families. Ministers need to ‘look at other ways to subsidise training, or GPNs and ANPs are going to be harder to come by’, argues Ms Allen.

Backlog of care for vulnerable children

As for child immunisations, the picture in general practice is that MMR uptake has ‘dropped quite a bit and we are seeing outbreaks of measles’, says Ms Randle. This could be explained by a reluctance from parents to bring children to the surgery for fear of their catching Covid, or be down to of a lack of trust in vaccines generally, she suggests.

The UK Health Security Agency reports that coverage for the two doses of MMR vaccine in five-year-olds in England is currently at 85.5%, well below the 95% World Health Organization’s target needed to achieve and sustain measles elimination.

Sharon White, chief executive of the School and Public Health Nurses Association (SAPHNA), says that despite the adverse conditions, nurses remain ‘absolutely invested in children… doing what nurses do – rolling their sleeves up, knuckling down and getting on with it with grit and determination’. But she says there is ‘a lot of catching up to do’ regarding immunisations.

Ms White suggests the drop in MMR uptake is down to the fact that, during the pandemic, children were not in schools, NHS services were stretched and there was also concern about presenting in clinical settings.

Denise Phillips, a matron at a south-east London NHS foundation trust and a former school nurse, is responsible for supporting school nurses. She says they are facing ‘more challenges than ever before’ in terms of the backlog of vulnerable children needing support, including those with safeguarding issues.

One school nurse in the south of England, who asked not to be named, highlights the detrimental effects of the cost-of-living crisis. ‘We’re seeing more food poverty than ever before’.

Ms Phillips says the attrition rate among school nurses has risen. ‘We have had to look at our service and put in critical short-term staffing measures to enable it to function and for nurses to have more face-to-face contacts.’

School nursing is ‘still suffering massive cuts – including from local authorities seeking to make cost savings – so the picture isn’t good in terms of meeting need’, says Ms White.

Despite these difficulties, the school nursing community ‘never fails to inspire me’ she says. SAPHNA has compiled an online resource showcasing inspirational examples of good practice, which include innovative approaches to managing anxiety, immunisation campaigns and tips on feeding schoolchildren on a budget.

Mental health problems in families have been exacerbated by the pandemic. A rising number of children are experiencing delays in their development including language and speech issues, and there can be long waiting times for CAMHS services, she says.

To help address soaring demand, and address concerns over mental health issues among pupils, NHS mental health support teams are now in place in around 4,700 schools and colleges across the country, with 287 expert teams offering support to children experiencing anxiety, depression, and other common mental health issues, and plans for at least 200 more across England.

But much more still needs to be done to put the wellbeing of children and babies ‘back on the agenda’, says Ms White.

‘The Government needs to stop cutting the public health grant, and reinvest in school nursing.

‘And it needs to reverse austerity – if children are hungry, they won’t attend school, they won’t learn, and our colleagues cannot even begin to address any of these other issues,’ she stresses.

The clear message from nurses is they want the Government to take steps to safeguard services and tackle the workforce shortage in order to prevent the difficulties they face from escalating still further. Ms Berry urges ministers: ‘Give us the support we need, back us up – show us you’re on our side.’

Until that happens, the current workload and staffing pressures mean it is more important than ever for school nurses, health visitors and general practice nurses to take care of themselves so they can keep doing their best for patients. As Ms White says: ‘Self-care has never been more important.

‘Nurses are exhausted and stressed, facing quite complex and really traumatic experiences. There’s no let-up; you need to care for yourself, so you can continue to care for others.’

‘Children’s services are pushed to the limit’

Helen Lewis, an ANP in general practice based in the South Wales Valleys, says:

‘We continued to see children and families during the pandemic and now we’re seeing more children than even before the pandemic, and they are coming in with typical childhood ailments.

‘Families are given the choice to come into the practice or have a phone consultation. But this choice is adding to workload – when you speak on the phone you may then still need to see them face to face. And when families come in, they are arriving with a “shopping list” of issues.

‘There’s a backlog in secondary care and we’re expediting referrals, including for ultrasounds and ENT appointments. Some patients also don’t understand why their child can’t be seen straight away – dealing with their frustrations also adds to the workload.

‘There’s good communication with our health visitors – they have an office in the surgery, so if we have a particular concern about a baby or child we can just visit them upstairs. But they are very stretched.

‘Uptake of MMRs is not brilliant because of historical concerns – but to help deal with this our team contacts parents if they don’t arrive for their appointments.

‘The cost-of-living crisis is starting to filter through into general practice. We’re seeing more families coming in who can’t afford to fill their fridges up. We have a wellbeing officer who has been coming to the surgery since even before the pandemic and who helps patients deal with issues related to their household bills.

‘There’s a workforce shortage without a shadow of a doubt. People left during the pandemic so we’re short staffed – recently I was the only clinician in the building. The Government needs to invest in making general practice nursing a more attractive option, and we need to get student nurses into primary care facilities.

‘Children’s services – as with other services in the NHS – are pushed to the absolute limit. We need to have an open line of communication with children’s services as a whole, including social services and foster carers, because children’s wellbeing is everybody’s business.’

Importance of care and support to new mothers

Mother of two Leanne, from Warwickshire, says the support she has received from health visitors has been ‘life saving’.

‘My second child was born just before the start of the pandemic. I was doing well. But when the first lockdown hit, the isolation triggered my postnatal depression – a condition I had also experienced with my first child.

‘I had constant support from my health visitor during the pandemic, both virtual, and face-to-face when it was allowed. Just her being there to listen was sometimes all I needed when we were all so isolated. And she was great at supporting my husband too.

‘This January, my daughter had her two-year mandated check and that was face-to-face. All mandated checks in our area are now face-to-face but I know that’s not happening everywhere – it’s a post code lottery.

‘I now run a small charity, and as part of this regularly advocate on the importance of health visitors. Their support was crucial for me, and I don’t know how I’d have lived without it.’

Natalie, who is based in the southwest, suffered from postnatal depression after the birth of her son during the pandemic. Since his birth, she has seen only one health visitor in person

‘After my son was born in 2020, I didn’t realise I was suffering from postnatal depression (PND). In fact, I dismissed suggestions that I might have been depressed as poppycock because I wasn’t sad: rather I was very angry or anxious.

‘Two years on, thankfully I’m feeling a lot better now. That said, I never received an official medical diagnosis because there just wasn’t the support from the NHS.

‘Following the birth of my little boy, I received two phone calls from health visitors but crucially no one visited me in person until recently. No one could have picked up on my struggles this way.

‘Funding for services for expecting and new parents is extremely important. Without the resources they need, they can’t give parents vital, in-person support.

‘What my family really needed was support from healthcare professionals, especially as first-time parents struggling under lockdown.’

Statistics: The Institute of Health Visiting describes the health visiting workforce as being at ‘an all-time low’.

- There were 6,278 health visitors in November 2021, a decrease from 9,376 in November 2016.

- NSPCC analysis of Public Health England data found that in 2021, one in five babies in England did not receive their 12-month health visiting review, with more than 106,000 babies missing out. Since 2016, there has been a 10% decrease in the proportion of babies receiving this check.

The cost of living taking its toll on families

- Around 9 in 10 (87%) adults reported an increase in their cost of living over the previous month in March 2022

- Millions of families are cutting back on food or missing meals altogether, according to data from The Food Foundation, which showed a sharp increase in children experiencing food insecurity, with

2.6 million under-18s living in households that do not have access to a healthy, affordable diet

Sources

ONS. The rising cost of living and its impact on individuals in Great Britain: November 2021 to March 2022. Link

The Food Foundation, Food insecurity tracker, April 2022. Link