When children should be sent for a Covid swab test

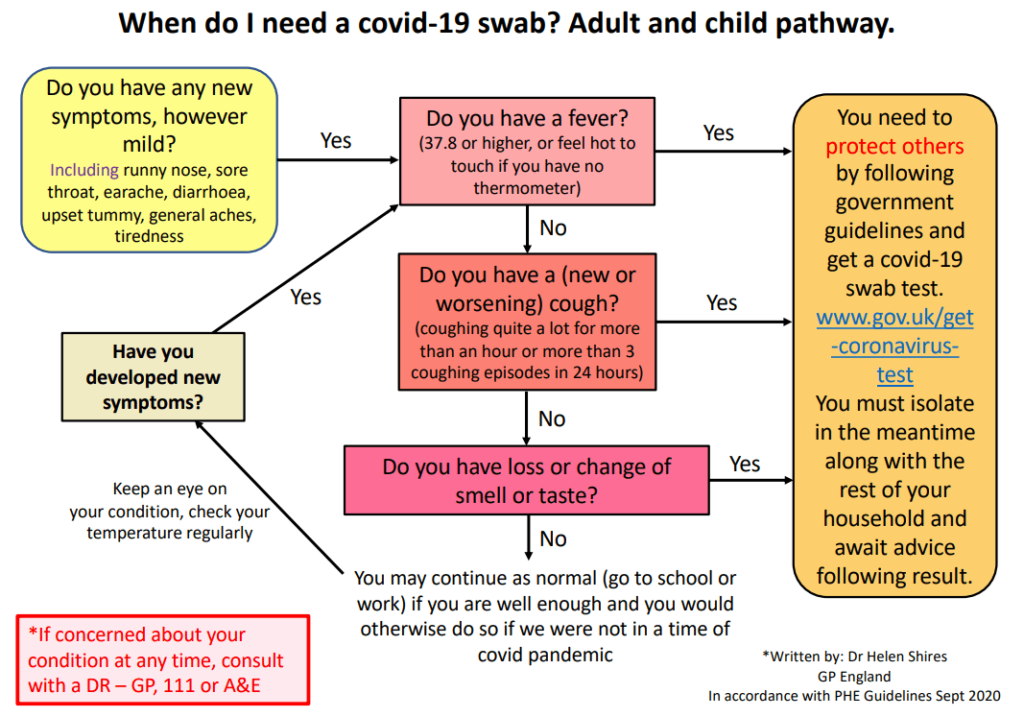

Dr Helen Shires explains when parents should be advised to take their child for a Covid-19 swab test. Below is a peer-reviewed flow chart she devised, strictly based on PHE guidelines, to help parents and clinicians make this decision.

If you happen to follow a parenting group on social media or belong to a Whatsapp group of parents in your child’s class at school – you’ll be aware of the discussion when term started around whether or not we can clinically distinguish between Covid-19 and the common cold or flu.

If that were possible, some patients could avoid the hassle and inconvenience of trying to obtain a swab test from a service that is already swamped (and this is before we have even embarked upon our usual flu / bronchiolitis / croup season).

Related Article: Prescribing in England to be led by a single national formulary

With a testing service that is stretched to beyond its limits, practices may feel pressure not to advise a patient who has a runny nose along with a fever or mild cough that the guidelines still state they need a swab test. In my personal experience, sticking to my guns and insisting that their child with a temperature of 38 and a runny nose needs a swab and to isolate (along with their entire household) goes down about as well as a lead balloon with the parent I am speaking to. After all, it is October, and little Freddy would normally have had at least two colds since term started, and he always gets a fever with a cold. Since Covid, ‘I know it’s just a cold’ are words that are guaranteed to send a shiver of dread down my spine, as they are frequently issued as the justification for having sent little Freddy into school for the past two days, dosed up with Calpol for his fever.

So, given the high number of colds we would normally expect to see around this time of year, how confident can we be regarding Freddy’s symptoms that, ‘it’s just a cold’?

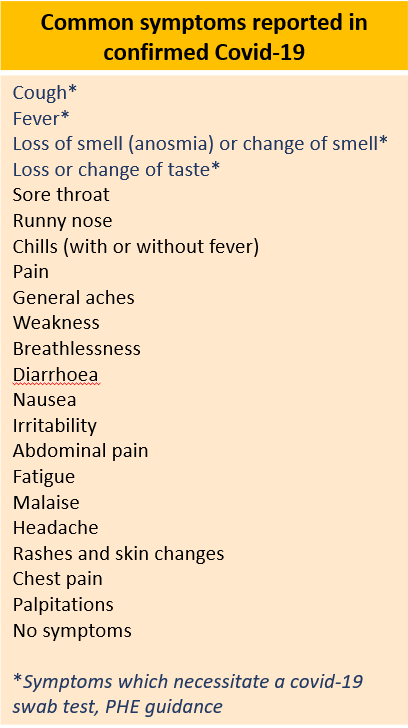

Covid-19 has been associated with an extremely diverse range of symptoms (see table 1 below), including runny nose. A multicentre cohort study published recently in The Lancet of 582 children and adolescents with confirmed Covid-19 from countries all across Europe, demonstrated the most common symptoms in this younger age group to be: fever (65%) and (not necessarily together) upper respiratory tract symptoms (54%); with approximately a quarter having evidence of lower respiratory tract infection; and just under a quarter (22%) with gastrointestinal symptoms. 16% were asymptomatic. (Article continues below).

Data analysed from Canada’s Public Health Agency for 121,795 cases of Covid in both adults and children reported that runny nose was as common a symptom as fever up to age 59, becoming less common with increasing age beyond that – although still reported in around 50% of patients with Covid aged 60-69 years.

Related Article: Advice on Guillain-Barré risk for adult RSV vaccine updated by MHRA

So how sure can I be that little Freddy’s symptoms are because of ‘just a cold’ when he has also had a fever along with his runny nose and a bit of a sore throat? Unfortunately, if over half the children and adults who get Covid demonstrate upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms, then I cannot be sufficiently confident to diagnose Freddy’s ‘cold’ on clinical grounds alone. It comes down to the simple matter of probability versus harm. What is the probability that he has a common cold? High. What is the probability that he has Covid-19? Low (but this probability will increase as the prevalence of Covid-19 rises in the population). What is the harm caused by my making a wrong clinical diagnosis of a common cold if he actually has Covid-19?

Before answering this, consider how we usually weigh up harm in primary care when deciding on a course of management for a particular patient. Pre-Covid (taking Covid out of the equation for a moment as it would complicate this scenario), if I were to see an otherwise healthy adult with pleuritic chest pain and a bit of a cough, I may consider them most likely to have a chest infection but choose to manage them as if they have a pulmonary embolism (PE) and send them to hospital. This is going to be inconvenient for the patient who will have to spend hours in hospital undergoing investigations, receive some harmful CT radiation, and experience stress and worry. Yet the level of harm to the patient if I miss their possible PE is substantial. In this scenario, the harm would be caused only to the individual patient.

If I were to wrongly diagnose Freddy with a cold and not insist that he follow the government guidance pathway to get a swab test and to isolate, then the harm is caused to others. Perhaps to Freddy’s grandparents, or the vulnerable family member of one of his class mates, or his school teacher, or his school teacher’s partner. The harm in this case can be as serious as death. Covid-19 deaths in the UK since the start of the pandemic are now just under 56,000, and this is considered a conservative figure given the lack of testing done at the height of the first peak unless the patient required hospital admission. ICU bed occupancy from Covid patients and Covid deaths have been rising once again. If the R number is around 2, and Freddy infects two others – who go on to give the virus to two people each, who also each pass it on to two others, and so on – how many people will Freddy give Covid to? (Answers on a postcard).

Related Article: Quick quiz: Management of COPD

Will pressure be put upon GPs this Autumn and Winter to give the advice that someone with a fever or a cough does not need a swab test due to the presence of a runny nose? PHE guidance does not state that the presence of runny nose negates the need for a swab. Should our clinical decision-making be based upon evidence-based PHE guidelines or on lack of availability of tests? I tend to think the latter is a government issue to solve and not a reason to deviate from best and safe clinical practice.

I designed a peer-reviewed flow chart (at the top of this page) based strictly upon PHE guidelines to help parents make sense of the confusion surrounding ‘Does my child need a covid-19 swab test if they have a cold? . The subsequent positive feedback after sharing with doctors’ groups on Facebook and widely on Twitter highlighted the fact that people find a simple flow chart much easier to follow than reading text. The following chart, which adheres to current PHE guidelines and can be used for both adults and children, also includes safety-netting and ensures that patients monitor their symptoms and refer to the flow chart again if they or their child develop new symptoms. This may serve as a helpful tool for use in primary care to direct patients to in order to reduce confusion and to clarify PHE guidelines.

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations

Click here to search a symptom